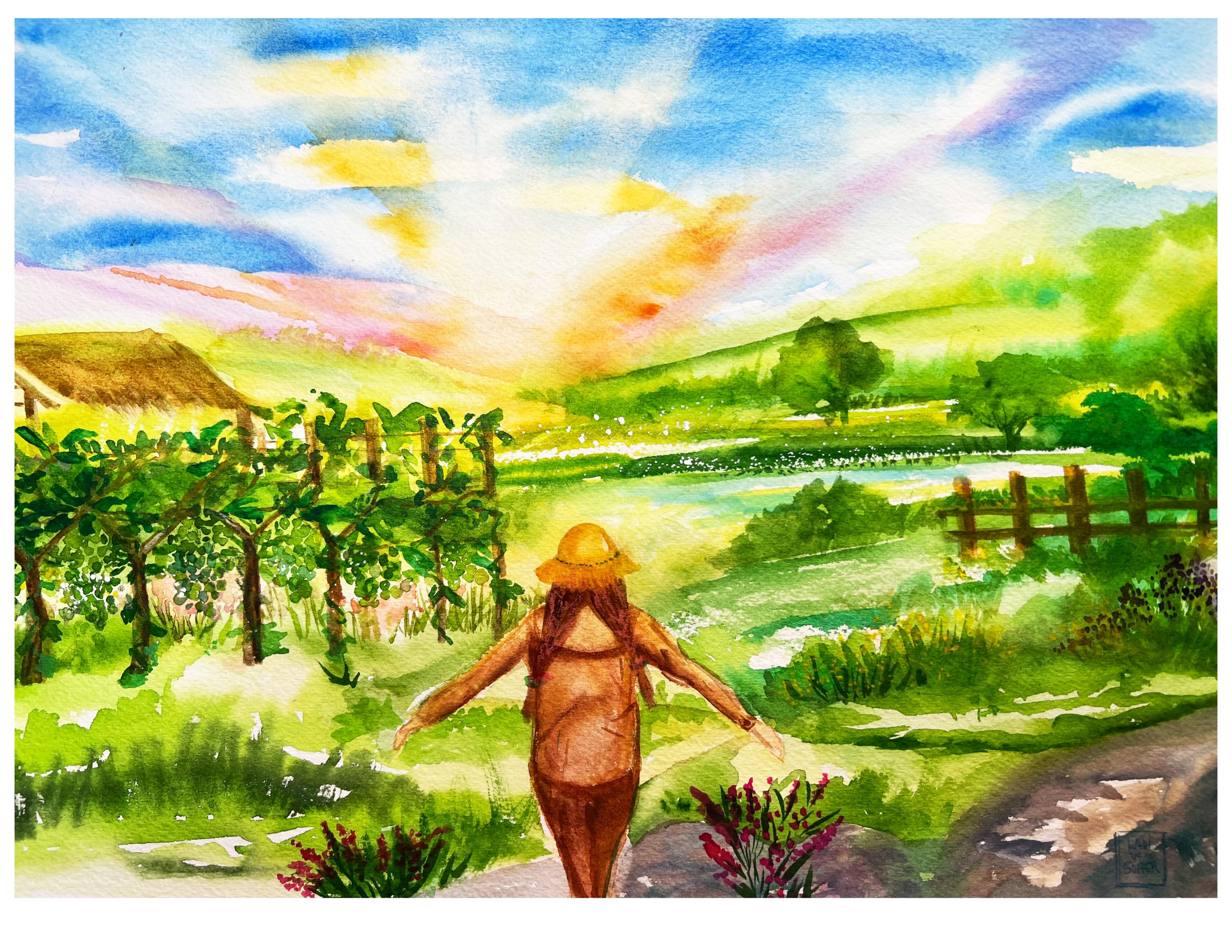

Yield

art by Lan Vo Soffer

Summer was pruning season. For $12 per hour–a princely sum in my early teens– I would spend two to four hours trimming excess growth off the grape vines at the winery down at the end of the road. I would cycle there as early as I could bring myself in order to beat the heat. Any longer than four hours, and the sun would be high in the sky, the packed earth baking. An aching back is what I remember most; that, and the sour smell of the rubber-and-cotton gloves as my hands began to sweat. When I would eventually pull my fingers out of the rough tubes and toss them back on the communal glove pile–were they ever washed?–my hands would be pale and shriveled, as though I had spent too long in water. Times like these were, in hindsight, among my most vivid and literal interpretations of a hot girl summer.

The area where I grew up has changed a lot since I lived there, which potentially explains the draw to write about it now. My family moved to a rural district a little outside Canberra, Australia, when I was in my early teens. The change wasn’t too much of a culture shock: I had long been a child who was either shut away with a book or desperate to be outdoors with animals, and rural living allowed me to pursue both these passions. I remember walking out to the ‘big paddock’–we gave all our paddocks similarly pragmatic names–with two visiting friends shortly after my family moved in. We spun around in the long grass with our arms outstretched, delighted by the freedom the space allowed us to run and yell and be silly with no one around to watch. In hindsight, this freedom of being both outdoors and at home, and of knowing there was absolutely nobody else present, watching, is a freedom I miss. I don’t let myself think too much about whether I will someday regain it.

The community in which we lived knew itself as a road. The houses were too spread out for there to be any suggestion of it being a suburb; rather, we lived on small farms, typically between 40 and 200 acres, that had in common one long access road that branched off from a highway. The road began in bitumen and ended in dirt. There were plenty of residents along it who I never met, although we did establish a road phone list in case we needed to alert one another about bushfires. I recognized people’s cars and based my opinions of the less chatty neighbors on whether they slowed down or not for horses. Most people did indeed stop and talk, sometimes for up to half an hour, the sun sliding down behind the grey hills. My mother would chat happily–ever a social delight–whereas I would sometimes grow twitchy and impatient. I’d try to hide it by busying myself with endlessly untwisting horses’ reins and dogs’ lead. Looking back, it is easy to marvel at how unrushed we felt.

One person who stopped frequently was the kindhearted man who became my first employer. R. owned the winery at the end of the road, where rows of vines cascaded down the side of a large hill, eventually giving way to the rippling ruts of sheep tracks that so often erode grazing land in New South Wales. I had always been curious about the winery: the purple painted sign at the entrance spoke of sophistication and interstate market ambitions, and the place itself seemed full of curios. When I went there, I never knew whether I would encounter the rifle shots of bird-scarers or the strikingly aggressive alpacas that would bounce after me, hissing and rearing from the other side of a tall wire fence.

R. offered me the job after I turned 13. Casual work at a winery is seasonal work, which suited my teenaged school holiday schedule well. In the summer holidays, I would trim the green shoots and suckers that appeared on the trunks and rootstocks of the vines, working my way up and down scores of rows, only to repeat the task as soon as regrowth had begun. I snipped off thin tendrils with stiff, poorly-sprung secateurs and ran the coarse rubber palms of my gloved hands over the rough trunks and graft unions, scraping away any buds daring to emerge. The inevitably daggy-but-sensible hat was not optional.

In the winter holidays, the hat was traded for a beanie, scarf, and puffy synthetic coat that zipped up to my neck. Joining a crew of about 7 other people–mainly older men with their own small wineries who pitched in to help one another–I would spend freezing winter days doing bottling work. This was essentially a factory line for wine. An enormous truck with the sole purpose of transferring wine from huge vats into myriad slender bottles would park at the mouth of the sheet-iron shed and hook up to one vat, then another. The soundtrack to our days was the cacophony of machinery, with glass bottles rattling and wine boxes stacking onto wooden pallets that would be picked up and moved using R.’s forklift. I remember Triple J radio playing incessantly into the late afternoon and my toes and fingers growing numb, despite double-socked leather boots and gloves. I was forever rubbing my hands together and flexing my fingers in and out of claw shapes, knowing I needed to grip glass dexterously as I moved bottles into boxes. When we huffed into the air, our breath would mist and our mouths grow cold.

Working at the winery gave me a decent amount of pocket-money, an early empathy for those suffering back pain, and an appreciation for how the most physical, difficult work can sometimes be the least well-paid. Like many people who have moved from highly physical casual work to office jobs, I am often struck at how an hour can easily pass with no tangible output from me. Unlike when attending a meeting or an employee development course funded by my corporate employer, when I worked at the winery, I was measured in terms of boxes stacked or rows of vines tended to. The idea of being paid $12 per hour–or more–to listen to R. discuss his vision for his business would have been inconceivable. Then again, that which might have once seemed inconceivable is, in some cases, already happening.

The winery closed several years ago. I do not know what happened to the other casual workers there, who would sometimes show up as familiar faces from one season to the next.

While knowing a place that marked my teen years no longer exists feels discombobulating, there is a broader melancholy at work when I realize many more wineries in regions like the one where I grew up will close in coming years. With temperatures rising and water becoming increasingly scarce, climate change is already negatively impacting the Australian wine industry and agriculture in general. Harvest dates are moving forward as grapes ripen early, but the duration of the vintage is growing shorter. Yields reduce, resulting in economic losses for growers and wineries. The wine regions as we know them are shifting south, and traditional wine varieties in south-eastern Australia will gradually be replaced by varieties better suited to harsher climes, or risk not being replaced at all.

The hill where I worked my first job is being divided into smaller blocks for more suburban housing. The antisocial alpacas are gone. The road has also become busier, and cars zip past at speeds reflecting the lack of official limits along such tracks. It is rare now for neighbors to roll to a halt and hang an elbow out of their window for a half-hour chat.

I do not write these things to lambast change. Planting new houses amidst the rocks and valleys stretching out from the road is a positive act, in that it enables more people to enjoy rural or semi-rural ways of life in a part of Australia that can easily house more inhabitants. I can rationalize such decisions, and believe in my own arguments too, even as I recognize that the road I once knew no longer exists in the way it once did. It’s a little like imagining all the Riesling vines I de-budded wilting in the heat, left to grow woody and wild – but reminding myself that maybe someone will go to the trouble of replacing them with Grenache.

My parents are selling their home and moving somewhere quieter and cooler; a smaller, more manageable plot of land with less fire risk. There will soon be no call to return to that particular part of New South Wales where we all spent so much time, much of it happily. Perhaps I will drive down the road again–maybe even very fast, in keeping with new local customs – in a few years’ time, to see how it has changed. Whether it looks drier, whether the creek is flowing. That said, it is curious how people sometimes put themselves in such situations in order to feel–what, exactly? Catharsis? Grief? It all seems so mawkish, almost scripted in its predictability. I plan to stay away, at least for now.

In the winter, however, when I feel the inland cold biting my exposed skin and settling in my limbs, I might take a moment to remember the ghosts of people I knew; people with whom I grew up. R. and his wife, who poured effort into the soil of that hill for so many years. The neighbors who stopped their cars and talked, or who waved from behind dashboards against which coarse-haired terriers braced their paws – and even those who didn’t. Or perhaps a 13-year-old girl wheeling her bicycle home along a rutted dirt road, balancing a box of wine on her bike seat – R. always let his workers keep the bottles that emerged from the factory line label applicator with wonky stickers. I remember so much still, even if my heart trips on occasion at the feeling that little details are slipping away.

Holding such details can feel like fumbling with a glass bottle, catching it by the neck before it smashes on the concrete floor. The hairs on my own neck standing on end. Strangely enough, nothing feels casual about memories of working in such a place, on an age-old hillside, that spent so long not changing that it eventually morphed entirely.