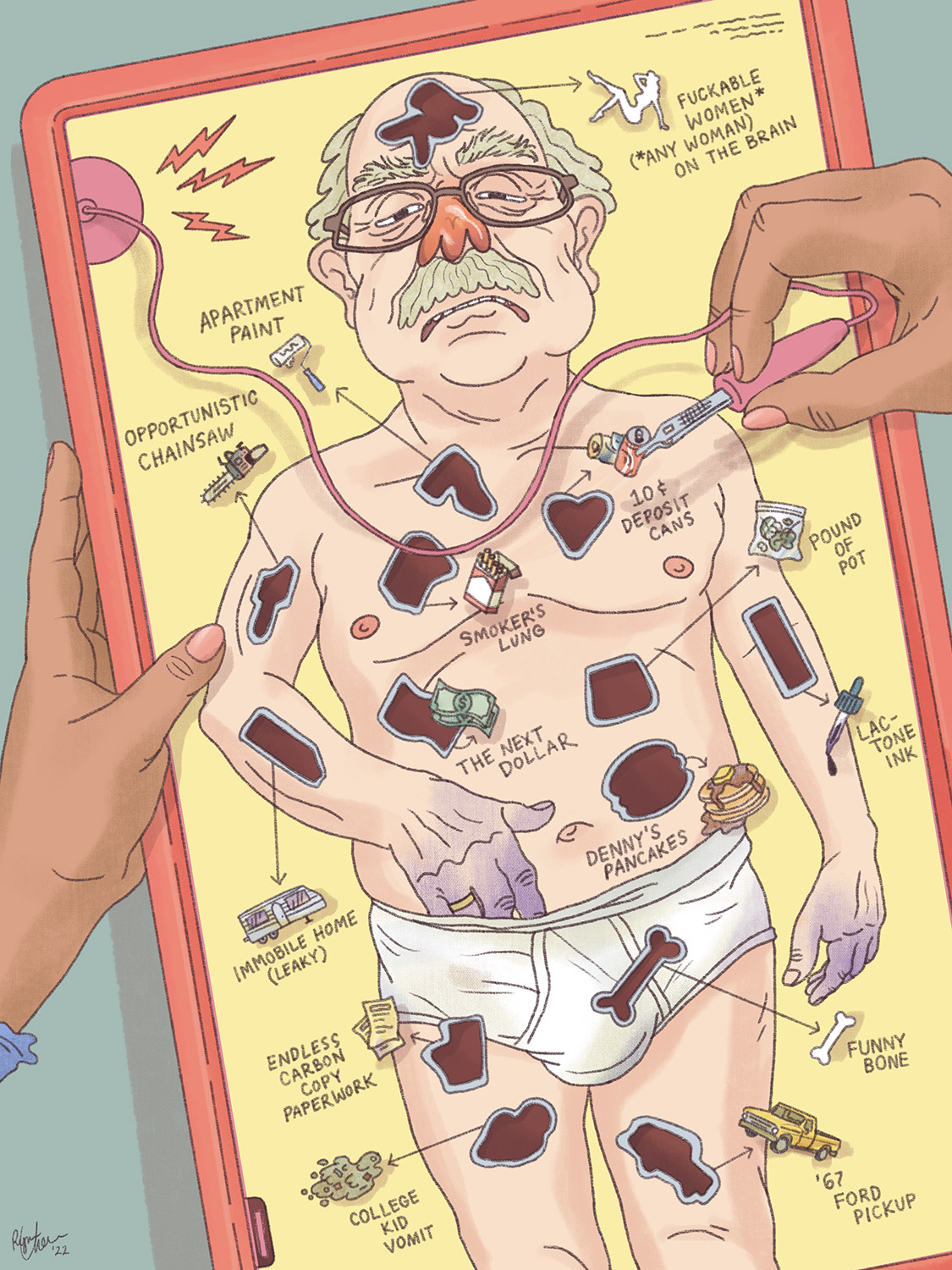

Uncle Rob Never Retires

art by Ryan Livingston

No one listened to Uncle Rob, not even his nephew, the boss of our crew of apartment painters. Not even Uncle Rob himself seemed to listen to his own rambling about women he wished to fuck, which was every woman. He loved indiscriminately. Any half-second glance at a silhouette would set him moaning, gripping his crotch in the backseat of his nephew’s Silverado, next to me. I wished swift escape for whatever poor woman stumbled into the conjuring of his imagination. Outside work, outside those endless apartments upon which we slopped the same candlestick-tinted paint, Uncle Rob was a regular at the Denny’s where my girlfriend waited sixty hours per week. Uncle Rob chain-smoked at the counter, emptying coffee mugs, filling and dumping ashtrays atop half-eaten pancakes. I was sure my girlfriend stumbled into his dreams, where she metamorphosed into a goddess draped in a golden-silk Denny’s uniform, her skin pink and pulsing under the buttons.

But Uncle Rob never fucked any one, besides his wife of forty-two years, who he only fucked on his birthday. A chore, he claimed. More work, worse than our infinite apartment walls to roll. The pleasure was in the imagining that trumped the trailer park where his roof leaked, where his LSD-dosing boys grew obese, where he’d parked the wheels of a once-mobile house and put it on blocks until death for the parting. Permanence the terminus of the fantasizing mind.

To spite his immobile home, Uncle Rob kept moving. You can’t die, he promised, if you’re working, which was why he cashed in his retirement from the bank where he’d worked for thirty years, where he’d filed carbon-copy paperwork by the yellow ton, his hands stained permanently violet from the lactone ink and PCBs he claimed had poisoned him worthless. He took his whole retirement in cash and bought a pound of pot and a yellow ’67 Ford pickup flashing a fresh paintjob that masked a ruined transmission. He and his old lady took a vacation north, across the Mackinac Bridge, all the way to Tahquamenon Falls, smoking blunts the whole way, until he’d converted his retirement into Ford exhaust and exhalation.

Uncle Rob’s nephew who bossed our painting crew had hired him out of pity. Uncle Rob and his purple hands and filthy mind lived dying-man minutes, the most precious seconds. And Uncle Rob and I scraped college-kid vomit off the walls, slopped more paint over mildewed bathrooms, each of us by the ten-dollar hour. But I was young, stashing more hours to burn. I prayed I’d never become Uncle Rob, who took a smoke break on the third-floor balcony, savoring this height at which he could survey every woman’s passing, love them blindly, equally, earnestly. Just beyond love was livelihood, and Uncle Rob kept working.

At lunch, through our shared smoke filling the truck cab, he moaned, and I expected another poor woman caught in his gaze. But he’d spotted a felled maple tree. Later he and his acid-tripping sons would return wielding chainsaws, would cut and split and sell firewood. After that, he’d loiter outside the MSU football game, the only man in the state who didn’t care about the score. Once the play time clock ran out, he and his boys would sneak in to collect ten-cent-deposit cans, garbage bags full, salvage waiting under the bleachers to be redeemed.

His nephew, our boss, was easy money in pity. Uncle Rob barely had to work. But he couldn’t help being good at painting, at any task asking his purple hands to keep moving, his filthy mind to dream ahead to this paycheck and that side hustle and the next dollar and the next.