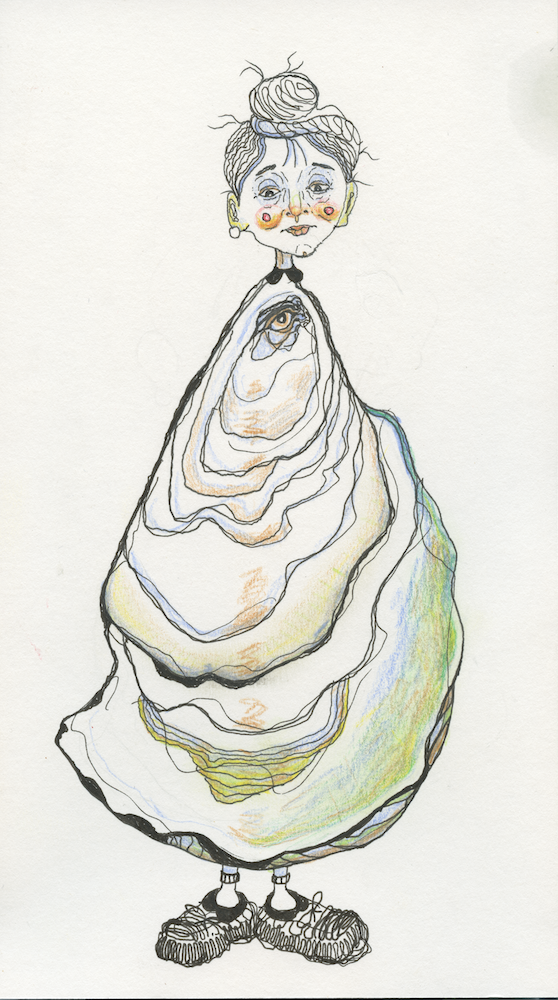

The Oyster Eaters

art by Robert Gemaehlich

He bears a plate of oysters and nods at me, his eyebrows raised. “Take one of these and feel it as it wriggles down your throat.”

“I’ve never eaten one,” I say. “I’m not sure I want to.”

He grins and hands me an oyster. It is fat and gray with a whitish blob and when I squirt lemon on it, it moves away. I raise it to my lips and bite and scrape it in my mouth. I can feel it resisting me. I swallow. I can feel it move down my throat, I think I even feel it in my stomach, reacting and then still.

“Welcome,” Michael says. “You’re one of us now.”

I will not be one of anyone, I say to myself. Still, the taste of it is in my mouth. Although I can’t feel it move, I know it’s in my gut, thinking. Waiting. Perhaps realizing its fate.

“I didn’t really want to eat it,” I say. I feel bad. It is not my fault. “How did you persuade me?”

“I didn’t do it. The oyster called out to you.”

I can feel a flush. I can feel a heat step through my body. I feel a quiver in my stomach, a tacit failure.

“The oyster forgives me,” I say quietly. I can feel the oyster’s forgiveness, but it is faint now. I want to atone for it; I want to assure it that the wrongness I have done is not the way I live, not really.

“You are one of us,” Michael repeats. “We all have an oyster in our belly.”

This is odd. This surprises me.

“Meet my sister,” he says. “She eats eels.”

“Patty,” she says, introducing herself and extending her hand. “And I only ate eels once. They were so lively I couldn’t sleep for a week. I don’t recommend it.” She held her hand up and burped slightly behind it. “But we are friends now.”

“How do you know you’re friends?”

“They tap. They tap every so often, letting me know they’re all right. The tapping has a distinct rhythm. I have adjusted to it. It keeps me company.”

“My oyster,” I begin, but then I don’t know where to go. “My oyster—”

Michael’s sister puts her hand on my shoulder. “I know how hard it is. There are places you can go, with other oyster eaters. They can talk to you. They can help you.”

Michael gives me a phone number. “These are the oyster eaters. They’ll take you in.”

“We’re meeting tonight,” I’m told when I call. “In a room with cushions on the floor.”

I go there and sit on a cushion. There are three women and two men. They are all kind and friendly and some of them rock gently back and forth on their cushions.

“I loved to watch my parents eat oysters as a child,” Jim says. “They fascinated me. I loved to see their open shells; I loved how they shimmered.”

“They are the ocean in a sip,” a woman murmurs. “Just a taste. As if it does no harm.”

“How could it be a harm,” a second woman agrees. Audrey. She introduces herself a few times; the others don’t call each other by name. Instead, they nod their heads in one direction or another. I nod my head too, though doing it—inside my head at least—gives me the sound of waves.

Audrey rubs her stomach. “It’s moving today, back and forth.”

“My oyster rears up and touches my trachea.”

“Can it do that, really? The trachea is not connected to the stomach.”

“Neither is the oyster.”

“There are only six of us?” I ask, looking around. There are a few extra cushions on the floor.

“It takes a certain sensibility,” Jim says.

“If numbers matter to you, we should include the oysters,” Vanessa says.

Of course we should. My oyster sometimes tells me stories in pictures. Scenes of the ocean floor. Fish trundling by. Shrimp on the stones. Captures and deaths. For those, there are sounds but they don’t resemble human screaming, which is a relief.

The oysters usually live in groups; they do not like being solitary. I understand from the pictures they give me that my oyster may indeed approve of me as a fellow being, though not a friend.

Vanessa rubs her belly. Jim puts his arm on her shoulders, trying to soothe her.

“This one is unhappy,” Vanessa whispers. We all look at each other. No longer at Vanessa. “Unhappy?” I ask, but I’m ignored.

“We’ll meet again in three days” Audrey says. We all rise quickly, even Vanessa, who needs a hand.

I wish we could meet daily. There is so much comradeship when we are together.

I am aware. My oyster is aware. There is something newly calculating in my oyster. I ask Audrey about it the next time while we wait for the rest of the group, which now contains Billy, an older man with stained teeth. She nods. “It’s so spiritual and yet an adventure. Give in to it, let it tell you what it needs.” She kisses me lightly on my brow.

We are a family. We have a certain look. Skinny but fleshy arms, wide bellies, eyes like dead clocks. But there is an air of expectation. When we meet, there is a little fever in our bodies, a little stretch that feels like hunger, though in fact we are seldom hungry because the oysters are expanding, filling up our stomach cavities. On certain days Michael brings more oysters and we sigh, anticipating the movements, the opening of the shells, the smell of the ocean. The oyster is reluctant to be showered with lemon, but it accepts it quickly with a shudder of delight, not terror. The scrape of the little fork against the shell is musical, the lifting up like a lover’s touch, and then the wonder that the tongue feels, and joy in the throat.

I long for nothing else. I long for more and when we sit after our feast, our eyes are brighter, livelier, more loving. The smiles require no words; we are wordless; we are speechless; we are the grace of oysters and the sea.

I spend all week longing to be there again, not knowing what the longing means, though I have heard of a special time to come for each of us.

It comes.

I feel less agile. I sit in my normal place and look around. The platter of oysters doesn’t interest me. I cough.

My coughing gets worse. I double over to clear whatever is stuck in my chest. The others lean in, watching me. I can feel how flushed my face is. I gasp for air. I lift up my head and give a great and furious cough and then it’s done.

They all bend over and sigh with satisfaction. This is the reason we are together, the reason for our love of the sea and the effort, the tang of the oyster and the delicate inhalation.

A pearl lies before us, white with just a touch of gray, perfect in its flaws.

My first pearl.