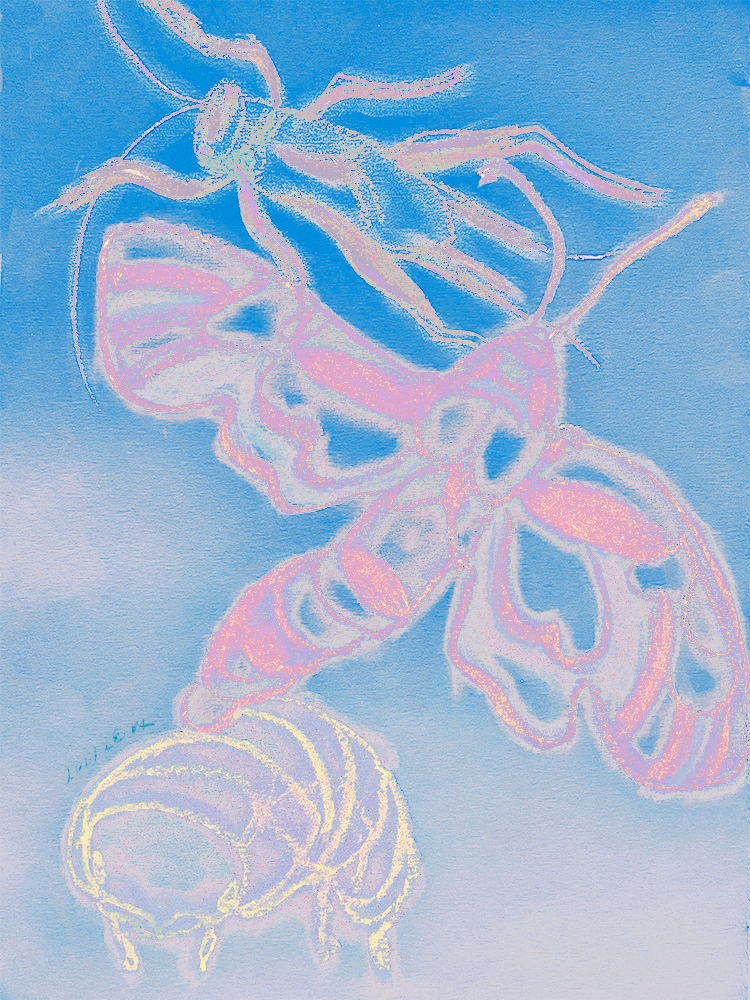

The Cricket and the Moth

Art by Ludi Leiva

Sometimes I pretend I am a woodlouse. My hijab overlaps my kurta which overlaps my pants, like a woodlouse’s segmented shell. I curl into a ball.

Eventually the other girls will stop kicking me.

This time is different. Words stop them. A boy’s words. “I’ve seen men beat their wives, citing Shariah,” he says, “but I don’t want to live in a Pakistan where the strong hurt the weak in Allah’s name. Do you?”

I uncurl enough to see the girls hunch their backs like ants and scuttle down the dusty alley.

The boy crouches. “Hi, I’m—,” and then he says more things, but I’m busy deciding what he is. His arm is thin as a reed as he holds out a hand. Pressed white dress shirt. Green-striped tie, loose. Rumpled black bowl cut. And talking all the while.

Chirruping.

I clap my hand over the laugh trying to jump out of my mouth. “You’re a cricket,” I whisper through my fingers.

And he smiles underneath his wispy fuzz of moustache.

“If I’m a cricket, what are you?”

I stand, dust off. His left and right earlobes are different sizes. “Well,” I tell his right earlobe, “I’m not really a woodlouse. I was just pretending.”

“Of course you’re not a woodlouse,” he says. “May I walk you to school?”

*

Cricket meets me along the road into town the next day. He talks so much that I shift my gaze from the green fields of wheat around us to his mouth to see if he ever breathes. He is fourteen years old, one year older than me. He also plays the violin, which is perfect for a cricket.

When we reach the alleyway behind the Shabbir Abad Electronics Store, where the girls attacked me yesterday, I show him the real woodlouse I’ve been clutching against my chest.

“Meet Arham,” I say.

Cricket bends over my hand to address the small crustacean properly. “Peace be upon you, Arham. I’m glad you joined us this morning.”

“Arham is in for a treat,” I tell Cricket. “We are learning about algebra today. Father says it is the art of secret numbers. The other woodlice under Arham’s tile are very jealous.”

“As they should be,” he says. Then: “Why were those girls kicking you yesterday?”

“Ants see other insects near their colony as a threat,” I say. “It is their nature.”

“Ah. And what’s your nature? Not an ant, clearly.” Then Cricket snaps his bony fingers. “I saw a bee earlier, black with bright purple wings.”

“Xylocopa violacea! Violet Carpenter Bee!” I shout. “A solitary species. No hive but a hole. Carapace like a beetle.”

“You’re not a woodlouse,” Cricket chirrups on. “Nor an ant. Are you a Violet Carpenter Bee, then?”

My laughter rings down the alleyway.

*

Every day when Cricket walks me to school, he has a new guess. Are you sunny like the Grass Yellow Butterfly? Are you bright like the Ladybug? Or perhaps you sting like the Banded Hornet?

“A Tiger Butterfly!” he says one morning. But he doesn’t even know the difference between the Plain Tiger, Danaus Chrysippus, and the Striped Tiger, Danaus Genutia, so I meet him after school by the florist’s fields to show him.

Past the sunflowers, waving heavy heads in the wind, a narrow patch of jasmine bakes in the sun, the white flower clusters shining like tiny stars. I inhale the thick, sweet scent, and imagine I’m one of the butterflies perched on the blooms, sucking up nectar.

“There,” I tell Cricket. “That one is a Plain Tiger. Orange wings with three black dots. And that one is the Striped. No dots, see? And the veins on its wings are thicker, like tiger stripes.”

Cricket hops over to the Striped Tiger, then the Plain Tiger, then back again. “You saw that from way over there?”

It is Cricket’s nature to ask questions he already knows the answer to. But he doesn’t get mad when you don’t chirrup back, which is nice.

“Well,” Cricket continues, “you can’t be the Plain Tiger or the Striped Tiger. They are so much alike that neither is singular. ” He talks more, his voice weaving pleasantly with the buzz of honeybees, the whine of the sun overhead, and the susurrus of wind through sunflower stalks.

*

We drop the subject of what insect I am after a few months. Instead, I watch the gauzy clouds overhead while Cricket tells me the math he is learning. The boys learn better math at their school, and he is one year ahead besides.

He lets me borrow his textbook when he doesn’t have homework to do, so I can teach Arham and the others.

Then, one day, he is cupping something tenderly in his hands when I meet him on the road. The wheat fields around us are stubble now, harvest done, and the morning sun is already hot.

“I found it,” says Cricket.

“What?” I ask.

“You,” he says, and he opens his hands to show me an Oleander Hawk-Moth, Daphnis Nerii. White striations marble its springtime green wings. “I found it on a window yesterday, still as a painting. Isn’t it breathtaking? No butterfly flittering. No spider, spinning silk only to lure its prey. No, it simply rested there on the pane, waiting for somebody to recognize its beauty.”

“Oh,” I say, because he is not looking at the moth anymore. Striations marble Cricket’s eyes too: amber, brown, and black. Have they always been so?

From his pocket, he slides a gorgeous springtime green fabric, suitable for a headscarf.

“I bought this,” he says. “For you. If you want.”

He turns around modestly. I check to make sure nobody is near, then change my scarf right there in the road.

“It suits you,” says Cricket, when he turns back.

Then he transfers the moth to my hands so I can study it while we walk.