Rupture

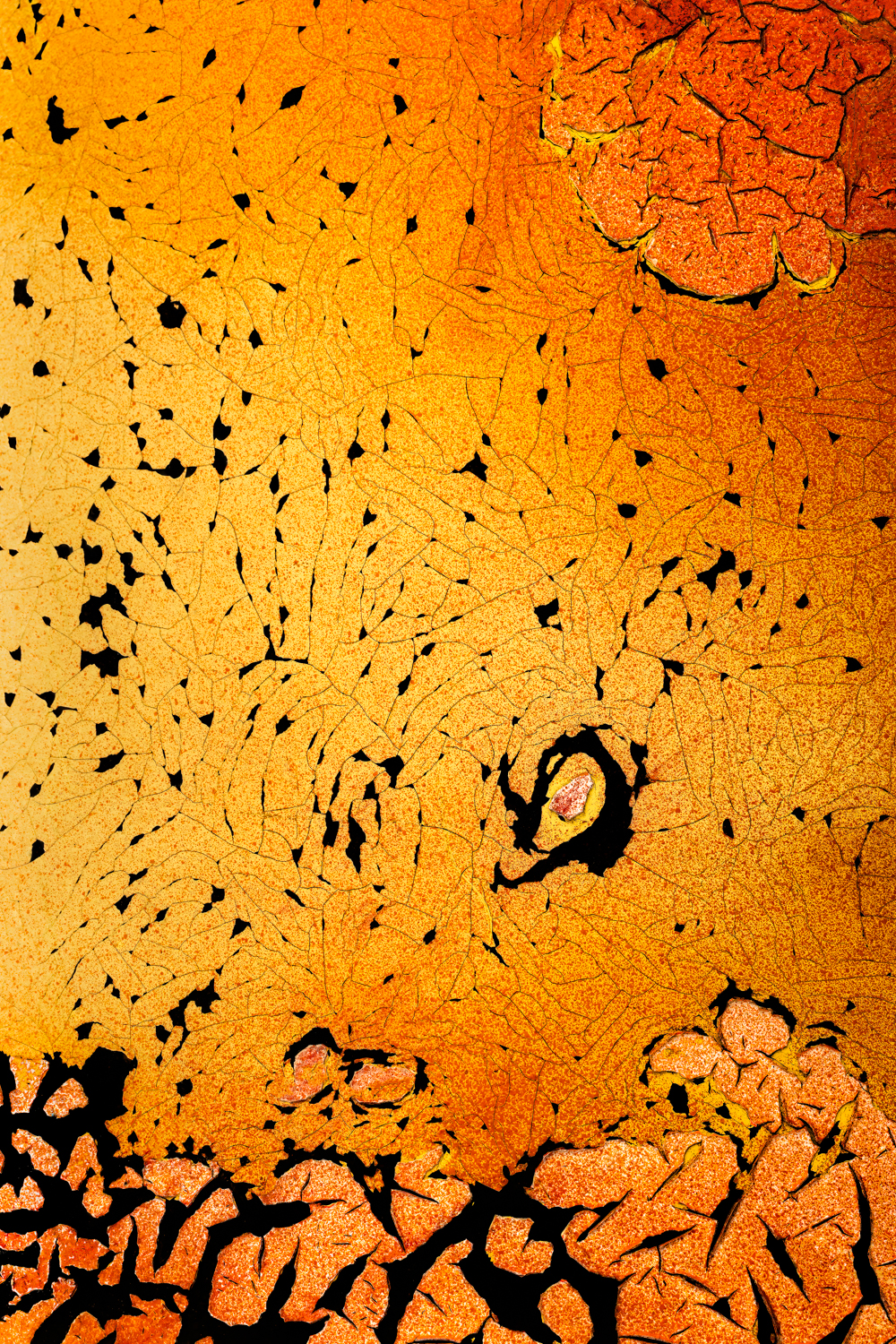

art by Ann Newman

“Don’t feed the cats,” my mother says, and I watch as she raises her hand to her face to move a strand of dark hair that won’t stay put in the warm Italian breeze. That hand. Mount Vesuvius smokes in the background.

A volcano is a rupture. I learned about it in school. I am ten years old, on a trip with my parents. We’ve traveled with a tour group from Gothenburg, Sweden, where we are living, here to Italy for the Christmas holidays.

We have just been shown casts of bodies, people who died when Vesuvius blew its top. One was a child about my size and next to it an adult with an arm thrown over the child’s body.

Now we are sitting on small, hard chairs at an outdoor cafe near the entrance to the archaeological site. My feet just barely touch the ground. I wonder what would happen if the volcano erupts again. I want the tour bus driver to call us back now, I want him to drive us away from here. But also, I love the cats, scrawny looking and wild but still coming right up to the table, hollering for something to eat, and of course I am going to feed them.

I am also scared of my mother. Still, I am going to “push it,” as she says. I drop a potato chip on the ground and the cat under the table begins to lick it, and two other cats run over and they lick it, too. My mother is fanning herself with one of the brochures the tour guide gave us. I drop another potato chip. More cats come. My mother looks at me, and my father sets his elbows on the round metal table and sighs. She laughs and shakes her head. Today is a good day, then.

On days that aren’t good I try to stay out of her way. I never know when she will lose her temper and explode, but one sign that an eruption might be coming is her rising voice, anger strangling past whatever she’s been trying not to say, or whatever she’s been saving up to say, or whatever she hasn’t known till just this minute she is so furious about. Whenever I hear that high-pitched tremble around my spoken name, I brace for impact.

Years later I will visit other volcanoes—Masaya wafting toxic gas from its open crater, one of nineteen active volcanoes in Nicaragua, and I’ll stay a month in northern California in the shadow of massive Mt. Shasta with its smoldering fumaroles. I’ll move to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where from the end of my driveway I can see one of the Three Sisters out on the West Mesa, part of a line of extinct young volcanoes that tore through the earth’s crust about 220,000 years ago.

I will look up information and read about volcanic structure—the conduit, branch pipes, throat, and summit — and when I do, I will think of Pompeii and of my mother sitting there in the Italian sun, her small head tilted, her eyes hidden behind tortoise-shell sunglasses. I will remember that was a good day and be glad for it.

I was a surprise baby, with sisters eight and ten years older. I know my mother resented the interruption. I know she had to work to love me. “I’ll give you something to cry about,” she used to say.

In the end, she does. I sit beside the hospital bed in the living room holding one of her hands in mine. From her mouth come short, dry breaths. She is beyond my reach now. By tomorrow she will be gone to ash.