Re-right or Re-write?

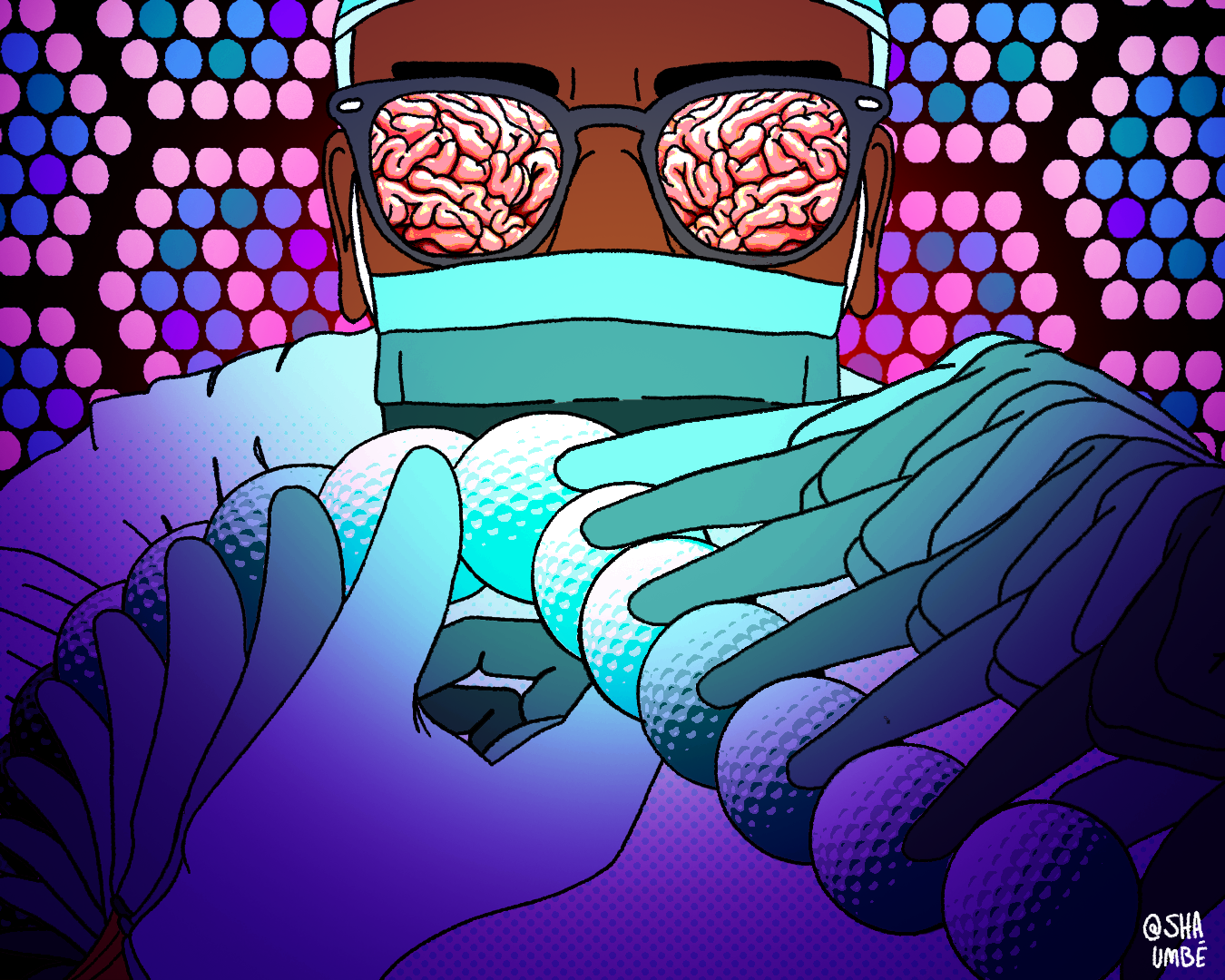

art by Shaumbé

When you first meet someone who will soon be wrist deep inside your child’s skull, it’s preferable to be able to communicate, to get those burning questions off your chest. I stuttered and spluttered like a dying car engine until I gave up and bawled into my hands and couldn’t look up at him. I remember his name is Dr. Singh from a flashback of him yesterday introducing himself as Carter’s neurosurgeon. He told me the only information he can give about the tumour is it’s the size of a golf ball. He was more patient than most staff, waiting for me to compose myself. When it became clear I couldn’t compose myself he gently patted my shoulder and suggested I ask the nurse for a pen and paper to write down questions for him to answer when he returns the next day.

I held Carter’s small, perfect head in my hands and it was inconceivable that something golf ball sized could be hiding in there like a stowaway. After Dr. Singh left I swayed Carter to sleep and with my free hand I used my phone to read about golf balls.

What makes a golf ball instantly recognizable are the dimples. Early Scottish players slowly discovered, through trial and error, that occasionally the older the ball the further it travels. The more dents and holes and scratches they had – and when these marks were not too big and not too small – it created a just about right Goldilocks golf ball capable of going almost twice as far as a smooth ball can travel. The dimples reduce drag, increase lift, propel spin and rotation. Each dimple has a depth of approximately 0.010 inches. The dimples are minuscule, but have a profound impact on the ball’s potential. I try to visualize the precision Dr. Singh will have to work with, when Carter’s head is cut open and part of her skull is removed – what any 0.010 inches of her brain which will be meddled with will mean for her future quality of life.

Golf balls have evolved over centuries with many thousands of people building upon knowledge to perfect them. Dr. Singh is coming to the operating room similarly with the generational accumulation of knowledge about removing pediatric brain tumours. If I were a better person, I’d have an upbeat positive attitude, and I’d take comfort in the symbol of the golf ball as an object that shows what we are capable of when we share information and work together over generations. But I’m The Mayor of Misery, it’s a fucking golfball and it doesn’t belong in a brain and I transfer so much fury onto golf balls, I want to hit them with such might that they’re driven out of our atmosphere and deep into space.

Chris needs to hear Dr. Singh speak. I imagined a brain surgeon to be unapproachable and unable to connect with mere mortals, to look intense and fraught with constant esoteric burdens that I could never comprehend. But there’s a calmness about him, his voice is soothing, meditative. You see his beard before you see him, grizzly and unkempt, his face shield can’t keep it hidden. He reclines in his chair with such carefree nonchalance, you believe that he would rather be here than anywhere else in the world. Chris isn’t answering FaceTime, so I keep calling him until he picks up. I plead for Dr. Singh to stay until Chris answers, and he gives me all the time in the world with the quiet confidence of someone in control. The kindness in Dr. Singh’s voice tells me he can spin the narrative of what’s about to unfold to offer a glimmer of hope.

“We are responsible for removing children’s brain tumours for over one quarter of the landmass of the USA,” Dr. Singh begins as soon as Chris answers. “Larger than any other hospital in the country, from Alaska to Montana to Oregon, they all come here, and you just happen to live nearby. I can’t promise any outcomes, but I can promise we’re the experts who will give your daughter better care than she can get anywhere else. The MRI shows the walls of the tumour don’t appear to have infiltrated too much brain tissue. Though it appears to be an aggressive tumour, so I’ll need to aggressively remove it all, which means removing some of her healthy brain also – that’s because tumours usually look the same as the brain itself. Luckily babies’ brains aren’t developed yet, so their brains can re-***** themselves.”

I don’t know if the word was re-right or re-write. These words would keep me awake in the nights that followed. I try to work out which one implies less devastation to her brain. If Carter’s brain has to re-right itself, I want to know how it has gone wrong, and what can be done to correct it. If Carter’s brain has to re-write itself, I want to know what her story would have been, and what her new story will become.

I ask what tool he’ll use to remove it, and I’m terrified to learn that the consistency of a brain is like jelly, so instead of a knife, brain surgeons mainly use a suction tube. I’m also full of dread to learn that tumours look identical to the brain. Dr. Singh reminds me that the tumour is made from the same cells. We want to think of the tumour as an invader, but it’s an extension of us, it’s kith and kin. In my mind, he would open up her head and a black, molten, tumour would be smoldering away, as distinct as an alien meteorite landing on the desert floor, easy to identify and intercept from the pink softness of brain tissue.

Now I imagine a glass trifle bowl full of translucent pink jelly jiggling by itself on an operating table. There’s some jelly, the size of a golfball, set in the middle that looks identical to the surrounding jelly. Attempting to leverage it out, how mindful will Dr. Singh be of the imprint of each dimple, what consequences come from a heavy handed excavation? How would Dr. Singh balance this with the risk of an overly cautious removal leaving one dimple not prised fully out, allowing the tumour to grow back, bigger, faster, more of them, a single cell inflaming a rampage.

“They find a way to reprogram. Adult brains can’t do this. If this operation were done on you or I, we would spend months recovering slowly. Babies are rockstars, their cells are new, they heal quickly. I’ll remove part of her skull. In adults we would need to use a plate. But luckily in babies, the skull is still soft and can be replaced, it should knit back together. Expect to see a C shaped incision on her head afterwards. There are always risks with surgery, but know that I’ve personally been removing brain tumours from children for a long time.”

“If it looks aggressive,” Chris pauses to catch his breath, “why don’t you remove it now?”

“Tomorrow is the weekend, and I’ll be honest, Chris, the weekend neurosurgeons are good, but they aren’t as skilled as our weekday team. Your daughter is in the best hands with our weekday team. I’ve scheduled surgery to be the first priority on Monday morning, 8 am.”

“Is there a chance she can survive this,” I spit the words out, “with no problems at all?”

“The removal of the tumour on the left side of her brain will impact the right side of her body.”

“Will she …” I want to know, will she be a vegetable? I hate that I can’t think of a word other than vegetable. I search for a word that won’t taste bitter after I say it. “Could it affect her cognition?”

“We can’t guarantee anything, Bernon, the tumour looks like it’s pushed up against the part of her brain that usually affects movement. Only the future will tell us. Usually, with therapy, weaknesses can be strengthened.”

“Have you performed this surgery and the patient fully recovers?”

“It depends on what you mean by fully. Have I removed brain tumours this size from kids and they’ve gone on to have no major issues physically and mentally? The answer is yes. But the brain surgery isn’t your biggest concern, we have a shot at removing the brain tumour. Prepare for the chemotherapy or radiotherapy, the recovery afterwards, the possibility of it returning – these will be your biggest hurdles. You need stamina, not just for the first few steps, but the entire race. Carter has a whole marathon ahead of her.”

I can’t speak, but in my mind I’m bellowing in his face that he doesn’t know my daughter, he doesn’t know that Carter eats marathons for breakfast.

He pauses and hearing only sniveling as the questions run dry, he says, “This weekend you need to rest. Prepare for Monday, you’re all about to start a marathon.” Then he does the unthinkable, he confidently reaches over to me and gestures to shake my hand. I haven’t touched human skin outside my family for 18 months – but the nakedness of this handshake is striking. He physically offers his hand, his skin, we exchange our bacteria with intimacy, the biggest taboo of 2021, as an unspoken attachment, the coupling of our hands signaling our trust in his ability to save our daughter’s life. But after 18 months of meticulously following every pandemic rule, I wanted to yell: you’ll be putting your hands inside my daughter’s motherfucking brain and you’re willy nilly shaking strangers’ hands! It felt like he had stuck his tongue down my throat, and then suggested bareback sex as he coughs into my face.

*

I’m one of those people you avoid because I always recommend podcasts to you even though you have no intention of ever listening to a podcast. Comedy, true crime, tv show tie-ins. I always have a new favorite I’m pressing onto people who aren’t interested. Chris hates podcasts so I often tell him about them in great detail and he always does a great job of pretending to listen as he looks at his phone.

A couple of months before Carter was born I discovered Grounded. The UK’s most listened to podcast through the pandemic. A new guest is interviewed each episode by Louis Theroux, chatting about their life as well as how they’re coping with the lockdowns and restrictions. I begged Chris to try this podcast. He eventually relented, asking which episode I’d recommend. I told him the Helena Bonham Carter one was best. It’s still the last podcast Chris listened to. In it she talks about her dad. When she was 13 years old, he was diagnosed with a benign brain tumour and a straightforward operation led to complications leaving him quadriplegic and blind. As Helena tells Louis, “His world had diminished, and my mum’s too as his carer.”

Raymond Bonham Carter’s 2004 obituary praised his ability “to remain profoundly interested in the world around him and to confront his misfortune without a trace of self-pity or recrimination.” I know deep in my bones that if anything happens to Carter I will be full of self-pity and recriminations and my interest in the world will be reduced to a ball of fury inside my body that I’ll never let go of. I’m supposed to be inspired by Raymond Bonham Carter’s perseverance but I know I wouldn’t respond to a tragedy in the same way. My obituary would read, ‘Completely gave up because the universe is a twat.’

Medical procedures sometimes fail. The ergonomics of a golf ball may have evolved to the exactness of precision – but if the player has an off swing, or the club unwisely chosen, or the wind suddenly picks up – then it doesn’t matter how perfect the ball is, it can drop into a bunker, disappear into the water, descend out of bounds, lost to no man’s land.