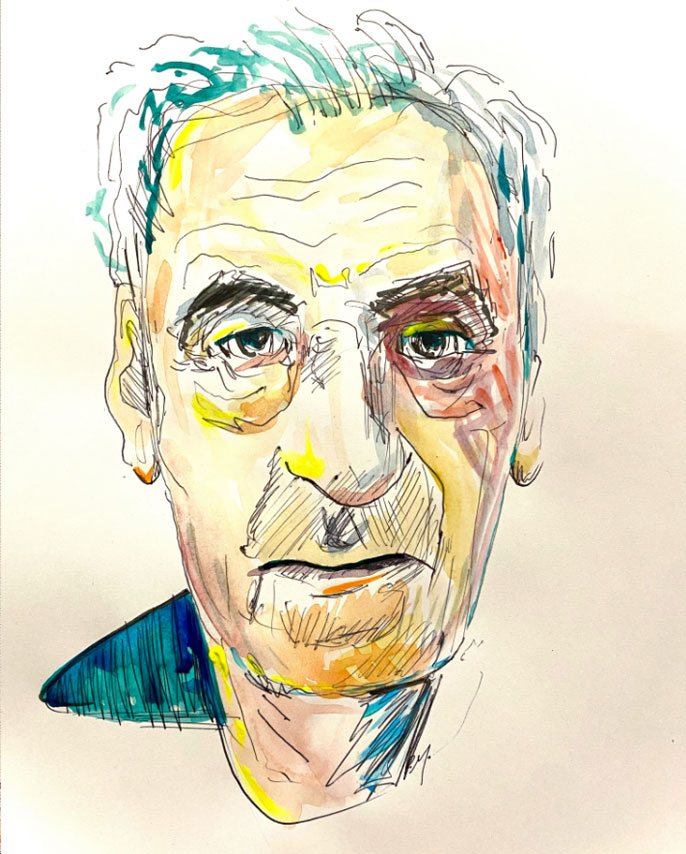

Ravilio Alla Eddie

artwork by Patricia Rounds Manwaring

Eddie Fanizzi gave my family two things: my grandfather’s name and a ravioli recipe. I never met the man, my great-grandfather Benedetto’s closest friend and a fellow immigrant from Genoa. But since we owe him, in part, for our patriarch and our pasta, I cannot help but regard Fanizzi fondly. Blurred by the haze of memory, his two gifts become difficult to separate. Spending time with Grandpa Eddie meant eating. Coins of salami dewy with oil. Prime rib smoked in a sawed-open barrel. And ravioli. Ravioli at birthdays and tailgate parties. Ravioli on paper plates and between toddlers’ gnashing fingers. Since it seems impossible to parse or rank Fanizzi’s contributions, I will start by describing the ravioli.

In classic Ligurian fashion, the dumplings comprise diaphanous pasta enveloping quarter-sized dollops of pork, beef, and spinach filling. Laced with butter-browned onions and parmesan, the finely chopped meat and greens transcend the presumed limitations of their humble forms. They achieve the savoriness of a Sunday meatball melded with the vegetal porkiness of Southern collards. Layered with a pancetta marinara and hefty handfuls of parmesan, the little pockets beg to be stabbed three or four at a time onto the tines of a fork. Benedetto was no nonna. His cooking skills were limited and developed late in life after he had immigrated to Northern California as an adult. He made two dishes. He made a pesto that substituted walnuts from the trees in his yard for pine nuts. And, after Fanizzi taught him, he made ravioli. But he was better known for making his young wife’s life an exhaustive misery and for tripping grandchildren with his cane.

My Grandpa Eddie was not like his father. He was the kind of man who now, six years after his death, remains difficult not to heroize. After his older brother gambled away all the family’s sheep ranches, Eddie went to work for the USDA. He regaled colleagues with tangent-riddled stories as they drove along the dusty backroads. And when his younger brother had a son he could not raise, Eddie and my grandma, Sherry, did. Further differentiating himself from his father, Eddie learned to entertain with passion and aplomb. He marinated and roasted dozens of legs of lamb for work functions and stirred vats of burbling polenta for neighborhood parties. He honed the ravioli recipe, diversifying the meats in the filling and adding red wine to the sauce. When Sherry finally convinced Eddie to replace hand-chopping with a food processor, he skeptically oversaw the implement’s inaugural batch.

Eddie’s funeral was the only family gathering I can remember where we did not eat ravioli. These days, my cousins and I amass in assembly lines to make them for our weddings. As we work, we nibble the parmesan rinds clean and pluck nuggets of rendered pancetta hot from the pot, just as he did. We plug the old food processor into the wall under my grandpa’s career awards, the Eddies still managing to swirl around our pasta dinner.