Gravitation

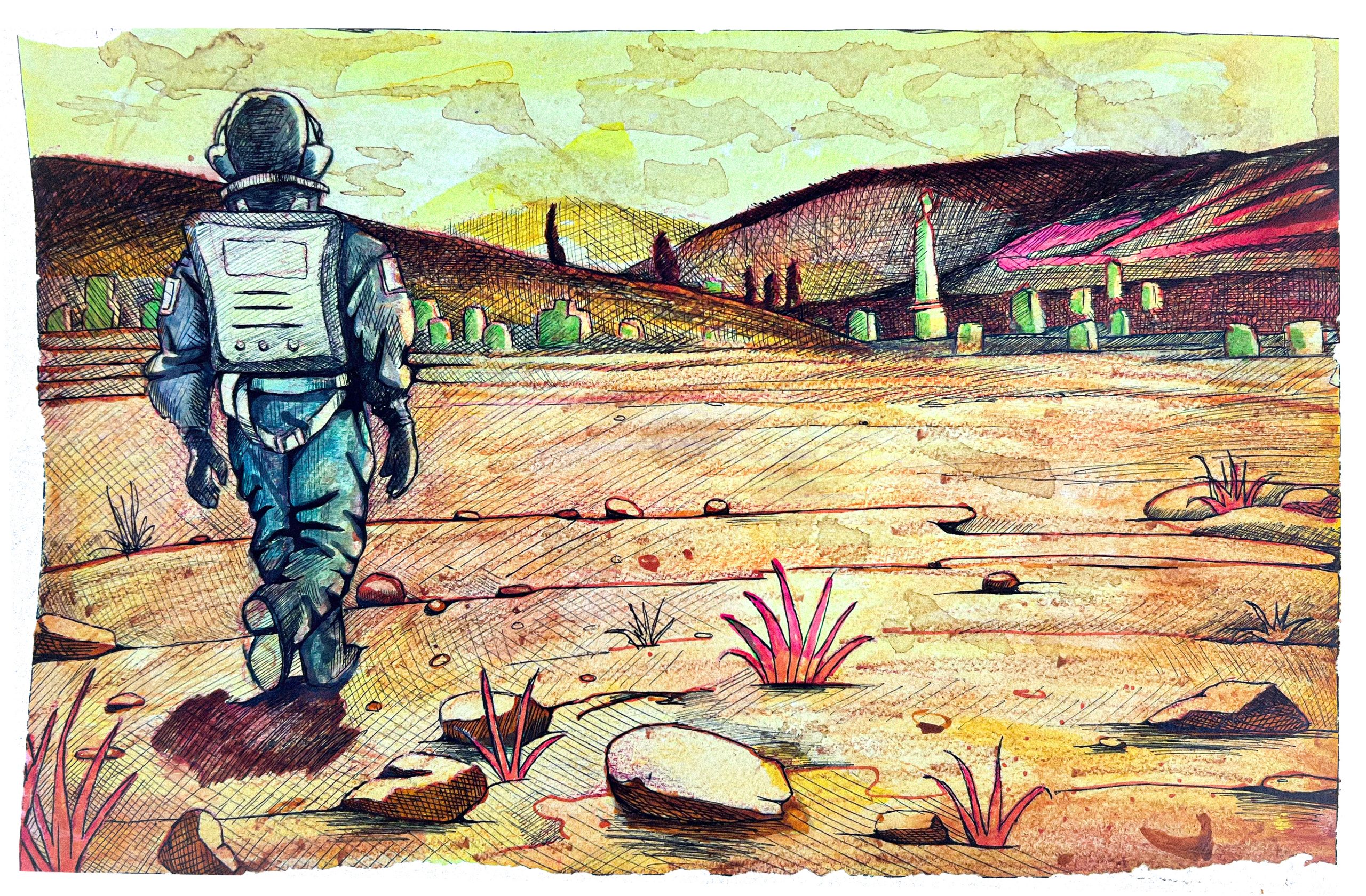

art by Gerard Pefung

My boss with blood cancer is selling his burial plot on Mars because he’s decided to have his ashes cannoned into space—all but fifteen hundred grams, which he’ll have pressed down into a diamond for his wife to wear. There’s more than enough of him to go around, he jokes, even though he’s only fat by Hollywood standards. He just likes the idea, I think, of having half his mortal remains on a perpetual journey through space-time, speeding outward in a straight line forever – while the other half stays here, nestled on the smooth, plumped-up chest of his rich third wife, who will outlive him by fifty years. Probably. But it’s none of my business.

My business is gravitation, which is another joke of his: I orbit him, closely and by contract, and can be spun out as necessary for various required tasks. On paper, I’m a “gravitational consultant,” which makes the astrophysicists on his latest space show cringe, as it should. He’s a big name, my dying boss. He’s won many awards and had many interesting scandals. His third wife is brilliant in her own right, like fire opals on scorched California earth: she is magnetic on screen, unstoppable in the four projects he bought for her. She left a co-star for him; he paid off a long-suffering second wife for her. And of course, he’s a tragic figure, or about to be. They’re deciding how to tell the press to ensure maximum coverage. He thinks they should wait until they’ve got a new project to promote; she thinks the cancer’s moving fast enough that they should get what they can out of it now. And the space angle’s a good one for the current show, which is on the bubble.

My job this week is to sell the Martian burial plot, which comes with the requirement that you wear a thin, full-body jumpsuit under your clothes every day that is the core piece of your eventual death garment: the five layers of farmed green spidersilk that they wrap you in before laying your small, biodegradable body out on the airless surface of Mars. People that actually live there have their own system of recyclers, but my boss’ burial plot is one of the permanent ones, the ones where famous people – or people that think they’re famous – mummify under the thin shroud of their death pajamas, so normal people can walk by on clear tubing pathways and look at them forever. The jumpsuit’s neck is embroidered with the phrase We go not blindly, but surely, knowing the way, which my boss loved at the time, but which now hits too close to home. The plot cost seven million dollars. It’s illegal to transfer it, so my real job is to line up another buyer for the burial company and make sure my boss gets his money back.

I have four prospectives lined up by lunch, and on my way to meet the first one, I pass a graveyard. There’s more of them around than you think. I wouldn’t stop, except I got so lucky on traffic that I’ve got half an hour I have to kill, and it’s sunny and not too hot, and I don’t get outside much. At one of the graves, a large family has set up lawn chairs and is blasting music and passing around samosas, and the aunties are having a massive argument about somebody’s wedding two years ago. At another, four old women are passing rice balls around and chattering like starlings. At another, a middle-aged man is sobbing into two expensive craft beers: he’s drinking one through the sobs and pouring the other out in dribbles. It’s chaos. Nothing dignified or stoic about any of it at all.

I wander until I find a grave with a nice view of sunshine, yellow grass, and other graves, and I sit down. My boss told me a story once about two actresses, both up for the part of a dying cancer patient. Dying’s great for your career. They flip a coin, and the one that gets the part moves to Hollywood, wins awards, wears diamonds. The other one moves upstate and takes videos of her three daughters running through the sprinklers in glittering teal swimsuits. It’s a story about being smart, my boss says. The actress that won the part cheated on the coin toss. She got everything she wanted. I’ve always liked that story. But sitting there, listening to arguments and music and heavy sobbing, the smell of rice balls and beer, I keep thinking about those imaginary children, wet and breathless, shrieking. Creatures of delight.

I don’t even like children. I like my boss. But I realize I can’t orbit him forever, not when he’s in space and his wife’s moved on, when the press won’t talk to me and I can’t afford to get to Mars. I won’t be the one to shoot him from the cannon, or to wrap him in the twee artsy garments of his death pajamas. There’s no point in visiting his corpse. And a Martian burial plot is only worth seven million, after all, which is pocket change to him but lots to me, and I’m good friends with the lawyers, and so I decide, right then, to break orbit and cut my losses, pull a nice reasonable amount of money from the burial plot fund that my boss won’t ever miss or even care about, and disappear to somewhere living, far upstate, where occasionally it still rains.