Everything You’d Ever Want

art by Nasimeh B.E.

The sorters, stockers, and cashiers call us the Village People because we’re regular shoppers here at Value Village. Mostly we are disabled, displaced, disturbed, diseased, old (which is also considered a disease), and every other dis that there is. We are all flawed, which is why very few of us are married. Who would want us? You probably wonder about those strange people in their sixties, never married, and still living in Mom and Dad’s basement. This is where you’ll find them. That’s not me, but soon enough you’ll see how I fit in.

The workers find us amusing—never imagining they could join us some day. I never would have guessed I’d end up here panning for gold among dead people’s cast-offs and wearing their nicely broken-in shoes. Once I read that well-heeled people hire someone to break-in their shoes. The not-so-rich use metal or wood shoe stretchers. Those contraptions turn up here every couple of weeks for about $3. Imagine being me, having a wealthy person break-in my shoes, almost makes me feel like a queen.

Speaking of which, once someone wrote an article about us for the local paper. They interviewed us about our biggest finds. I was dubbed, “The Value Village Queen.” Although it may have been about what I said rather than what I found. “Everything you ever want or need in life will eventually show up here,” I’d said. I did find a few treasures and told them about one: two cases of pre-stamped business-size envelopes, 500 in each box. One ounce of postage carries about 6 sheets of paper. This was a writer’s dream. The two boxes, total, cost me $4. I took this as a sign that I needed to keep writing—like it was my destiny. I used them all up in a little over a year. Then I was broke again and my writing remained hidden in the dark pages of notebooks. Not the nice leather-bound ones that my rich writer friends use. No, my notebooks are spiral bound, ten for a dollar at Target’s Back to School Sale. “But is your paper acid-free,” they’d ask. “Hell no. These pages have so much acid it’s amazing I’m not hallucinating more than usual.”

That reminds me of some of the other things I found at the Village that I didn’t tell the reporter about. One day I was walking down the picture frames, cards, and books aisle. Suddenly, I smell pot. I look around to see if the pothead is one of the Village People or someone I don’t know. I see that I’m alone. I followed my nose to a fiber wall hanging that was tan and actually sticky from years of smoke. I pictured it on a basement wall above the sofa getting soaked, day after day, until finally the smoker died and it ended up here for $2. In the past I found dope pipes mixed in with Legos in the children’s aisle. I’d told the manager who said, “Thanks for pulling this.” The wall hanging wasn’t going to harm anyone so I left it. I could just see some freak using it as a giant tea bag.

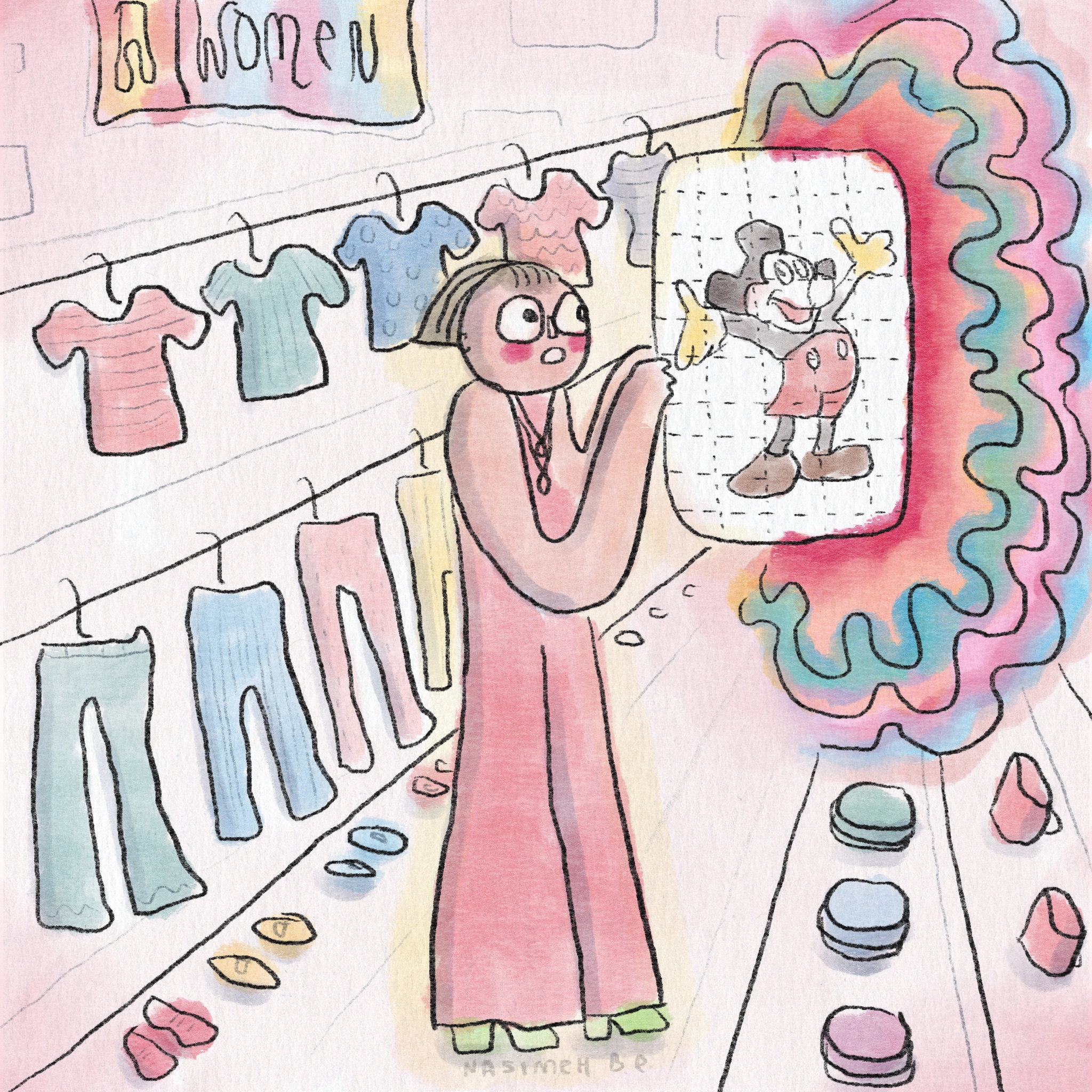

Then I saw something that made my heart jump. It probably came in with the wall hanging. On a pin among the cards was a package of about 10-15, 8 ½ X 11” sheets of Mickey Mouse blotter paper. There were about 100 images per sheet. Each mouse was outlined in dots to show where to cut. I looked close and could see that a drop of liquid had been put in each square. I had about 1,000-1,500 hits of LSD in my hands. It would cost me 75 cents—half price day. My hands were shaking. Years ago LSD was my weakness, my drug of choice. At that moment I actually thought about William Stafford’s poem where he finds a pregnant deer lying on the side of the road. He has to decide if cutting the live fawn from its mother’s side is the right thing to do. A deer raised by humans is a hunter’s dream or a zoo resident. The fawn will never have a natural deer’s life, bounding over the fields as if on springs, or standing quietly among the trees nibbling wild apples. So William kicks the doe over the edge.

I too had to think about what the future might look like. In my acid days I stared for hours, grooving on a tropical fish tank; stumbled around parties looking for the punch bowl of windowpane Kool-Aid and skunky brownies; visited the States Fair animals and read their minds; and watched my lover’s skin turn to putty gray with each pore hiding something vile. How would my daughter, whom I love, appear to me? Would she look like a possessed elf? A Rumpelstiltskin? Would my husband, whom I love, become a field of blackheads sprouting like asparagus? I had no idea how my mind might twist my happy, cupcake life into a Salvador Dali melted nightmare. As much as this sounds fascinating, even a bit cool, I just couldn’t do it to them. I loved them too much. I wanted to remain the mother my daughter thought I was. Yet, the temptation was such a deal—only 75 cents—a fraction of a penny per eight-hour high. Booze costs much more and delivers far less. Not to mention the carnival-like LSD slide show, complete with living freaks. “I thought hard for us all,” like Stafford said, and hung the blotter acid back on the peg for some other soul who wants life with a little more sizzle and has nothing to lose. Then I turned my back on it all and walked toward the future to check out the dead people’s books.