Dog Fever

art by Daniel DuBoulay

Antonius tells me the important thing about these feathers, which we’re currently plucking from a rooster’s anus, isn’t that they come from a rooster, but that they’re red.

“Only red ones do the trick for dog fever,” Antonius says. “Helps balance out the yellow bile.”

I write that down, even though I have no clue what yellow bile does or what it even is. But Antonius is probably right. He’s the best physician in town. I’m just a trainee. Years from starting my own practice. A wannabee. But everyone has to start somewhere.

Antonius reaches for the rooster’s anus, rips feather from skin. He sniffs his fingers and nods approvingly. The rooster, it should be noted, is super dead. No pained shrieks or anything awful like that. We’re not trying to torture the poor thing. I’m told the rooster’s reward for this sacrifice will be in its next life. At least that’s the hope. That’s the line.

“Why does it have to be from the anus though?” I ask.

Antonius gives me a look. “Are you questioning a thousand years of medical wisdom?”

“I was just asking.”

He rolls his eyes and hands me the feathers, which I enclose in a leather pouch. We’re supposed to mix the feathers with poppy juice and pulverized lily bulbs to make a salve. I’m told vomited blood also works to combat yellow bile if it’s combined with good wine and a vulture’s lungs, but vultures are notoriously hard to wrangle. So this will have to do.

“Look,” Antonius says. “I don’t want to quash your curiosity. It’s a virtue. A critical part of the whole education process. But you’ve got to trust me on this.”

I didn’t have much of a choice. Our village was in pretty deep shit. Sick dogs howled nonstop. One of them, a mangy, starved thing, not too far away from us, trembled in the midday sun. It shambled down the dirt path, moving this way and that, like getting yanked by a puppeteer. The thing let out a throaty bark, then a whimper. Even from this distance, I saw the froth dripping from its open mouth. Starting from the end of spring to the beginning of summer, nearly all the dogs had contracted the fever. We’d issued a warning advising children and the infirm to take up sticks to defend against attack. There’s been a lot of dog-on-stick action.

But it’s not the dogs’ fault that they’ve gone mad.

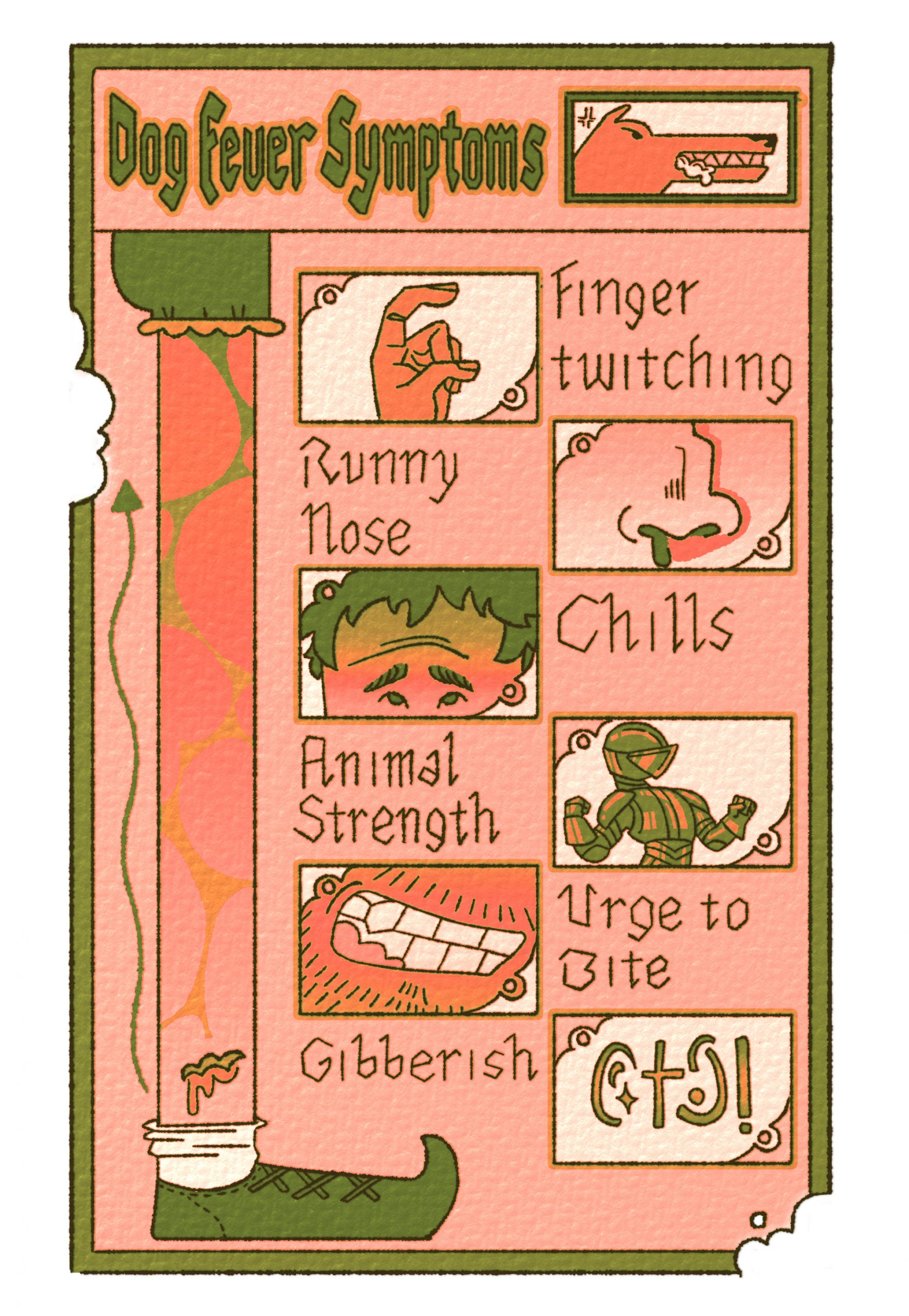

The sickness started, according to Antonius at least, after an infected bat found its way into the Vestal Temple. Started spasming on the ornamental tile. A girl, young Lavinia, daughter of Lavinius, had gone up to it, bringing it to her chest like a newborn—and what a good mother she’d have been! Just a scratch. Nothing to it. But that was enough. Once the fever took hold, we’d needed to restrain her, an animal strength coursing through her frenzied veins. She screamed gibberish, snapped her tiny jaws at us, searching for a way to sink her baby teeth into our skin.

Antonius says the malady climbs up from the spot of the wound and makes its way, inch by inch, to the brain. There, it takes root. The symptoms don’t present until it’s too late. The moment you have a twitchy finger, or even just a sniffle, it’s over.

We don’t tell you that, but that’s how it is. You refuse to drink water or wine. Can’t bring a cup to your lips, your hands are shaking so bad. Even if we strap you down, force you to drink, you’ll start gagging. Spit it right out.

Antonius has a treatment for water fright. Not so much a cure as a last ditch effort. If you’re infected, we throw you into a tub. Then comes the unpleasantness. We have to hold you down under the water until, completely exhausted, you sink. Maybe your mouth sighs open, water flows in, goes down your throat. Or maybe you drown.

Pick your poison, I suppose.

“Damn disease,” Antonius says. “Why do the gods test us like this?”

“The gods are jerks,” I say.

“Can you not blaspheme?” he says. “You know it just invites more punishment.”

“Sorry, gods,” I say, looking skyward. “Didn’t mean anything by it.”

It’s all for show. I don’t believe in the gods. Why would there be divine beings on a mountain way up high? Sounds dumb. I believe in life. Its awesomeness. Its sanctity.

“Well,” Antonius says. “Let’s hope apologies help. This next one’s a doozy.”

Our patient is another kid. A boy, Publius Maximus, of patrician blood. Dog fever takes all kinds. Kids, especially. I think it’s their innocence that does them in, their willingness to comfort the fevered dog, the spasming bat. Compassion is their undoing.

What kind of lesson is that?

In the atrium of house Maximus, we find Publius splayed out on a divan. He already looks half-dead, pale and thin with a tremor in his lip. Antonius glances to me. We both know, in the end, what will happen. This disease leaves no survivors.

Publius’ mother loudly weeps by the central fountain. Publius the Elder, his father, yells at a slave to go fetch us water. “Oh, doctors,” he cries. “You must save my boy!”

Even though I’m not, technically, a physician, Antonius doesn’t correct him. He simply kneels down to apply the salve to the bite mark on the boy’s hand. “This will help stabilize the humors,” Antonius says. “Flavius, massage the boy’s scalp for blood flow.”

I knead into his scalp, stroke his soft, thin hair. Publius, coming out of his stupor, stares up at us sweetly. The poor thing. He thinks we’re here to save him.

Despite everything, I find myself hoping he’s right. I wish I could believe that compassion will be met with mercy. That the gods are real after all. That, somehow, they’ll allow us to perform a miracle.