A True Story About the Best Neighbors in the World

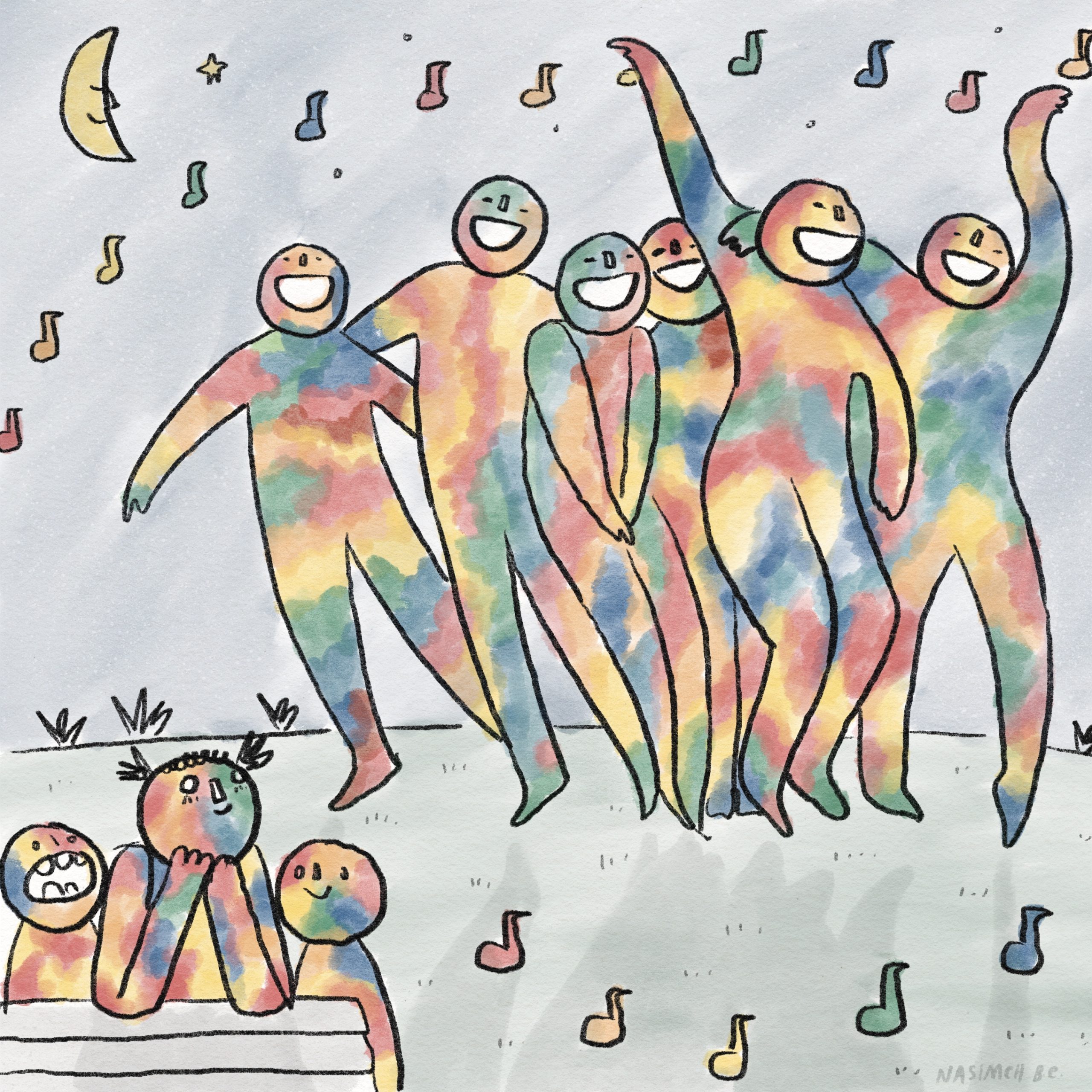

Art by Nasimeh B.E.

The party is still going on.

It’s been twenty-four years since I took my leave, but chartreuse chickpeas still intoxicate the air. Quadruple-entendre’s wriggle through reggae. And down the road, gigolos make their own justice.

When I was young enough to believe that life was based on a true story, I received the best neighbors in the world. I had wanted my grandparents to move into the house next door, entertaining visions of blueberry muffins and cartooning beside my grandfather. Instead, we would have the Carters from Trinidad, which someone described as a “potato chip crumb in the sea.”

Patriarch Reginald was the longest man I had ever seen, ecstatic with arms that boxed the clouds. His legs had no bones, and his eyes were large enough to adore the world. He rejoiced my heart when he laughed. Reginald’s hair was as cheerful as mine, and someone said he was an engineer.

While Reginald chaperoned smitten children at the picnic table, Nilda and her college daughters coaxed light onto the stoop. I never saw Nilda wear a color more timid than magenta. She talked about Jesus as though he was pouring himself a second cup of coffee. “We had a talk today; oh, we had a talk!”

Millie’s pigtails laughed, and her voice ran arpeggios. She brushed my hair and showed me how to make fancy bracelets from thread. Gita was chenille and calico, always last to speak, but she loved me before I earned it. She drove a powder blue Beetle, and I decided that I would drive one, too. They were interested in a full account of my day at elementary school.

Reginald and my father were instant friends, their buoyant banter rippling the driveway. Bus stop parents muttered about Reginald’s Audis, but they didn’t know anything. Reginald’s legendary legs ran to the rescue when Dad was stung in the eyelid by yellow jackets. Reginald’s picnic table had a place for me.

I wanted to live inside their voices. Turmeric turned everything gold, and I gulped down the scents of the Carter kitchen as though I could save some for later.

Someone said that Trinidad had only summer, but the Carters shaped our seasons. Winter was the Church Sale, when Nilda covered her walls with tapestries and Last Suppers, disciples as variegated as soup beans. I fingered the brown wax John and radish-red Andrew. Nilda gave me small angels for free.

My mother adored the Carters and saddled home with inspirational armloads. Nilda was never so pleased as the year Mom bought a framed 1 Corinthians 13 sampler large enough for the National Cathedral.

“You know how to read that, Susan?” Nilda asked.

“What do you mean?” My mother walked the earth toting The Ultimate Book of Bible Verses by Topic, and the section “Love of God, the” was grey from consultation.

“The Word will work if you work it,” Nilda urged. She pointed at the verses. “Love is patient, love is kind. Love is God. God wants us to be perfect as God is perfect, yes Susan?”

“Yes.”

“You change it to your name – Susan is patient, Susan is kind.”

“God help me.”

Nilda nearly smiled. “Susan is long-suffering. Susan never fails. You pray that. You see where you need to go.”

“I have a long way to go, Nilda.”

“So do we all. But praise the mercy.”

Mercy drove the year for the Carters, and as spring stretched its arms, the children came. They had names like Mercury and came from TV-news places like Newark. Reginald and Nilda’s “blessings” began arriving from the first year.

“To whom much is given, of them much is asked,” Nilda was prepared for all who asked. The bus stop parents were concerned. “We didn’t agree to be the Fresh Air Fund,” the father with the cigar said.

My father was elated. A child of sixty-eight, he introduced himself to the blessings under the guise of introducing me. He made them guffaw and called them “delightful.” Mercury was the most delightful. The backyard toads liquefied him with their ludicrous belching, and we held hands and made clover lanyards. He would not go home until I learned to hula hoop.

The blessings remained into midsummer, the highlight of the Carters’ year and mine. Right around my mother’s birthday, the world was remade by the party.

When you are young enough, you trust that every life is based on a true story. As carloads of joyous strangers filled the yard, I assumed we were about to experience something wonderful. For once in my life, I underestimated the case considerably.

Nilda had spent days in the kitchen, commanding vats of neon wonder-orbs I had to be informed were born as the same chickpeas in my grandmother’s Sicilian soups. Blankets of dough spun like saucers, translucent pancakes that smelled like sacraments.

The blessings and I were tasked with shepherding smaller children whose numbers surged into the night, shrieking and slurping Capri Sun and attempting to annihilate one another. TeKeisha rocked them on the porch swing, and I instructed them to each find ten yellow dandelions. We made them trade their bounty. “Give him your best dandelions,” I commanded an F5 hurricane in a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles tank top. “Now you give him yours.”

“Now you belong to each other.” I have no idea where I got that, but the turtles got it.

The sky would be getting dark now, celebrants on their third Corona and fifth flying saucer. Every year my mother marveled that she “always hated curry, but Nilda’s roti is heavenly.”

My father was long lost to us, the bookish elderly Englishman turned to flame. I felt dizzy with pride, watching him whirling and pink among island saints. This was a true story, and my darling, dorky Dad played a supporting role.

Everyone waited for the night’s high moment. It was so worthy, Reginald couldn’t help but ensure it recurred at least ten times. Shouts whooped supreme as the refrain began: “Age is just a number…”

Soon they were dancing, the engineer and the Englishman and the blessings and the turtles. Moving as one, they sang along about the joys of being ancient. It would be years before I tracked down Mighty Sparrow’s filthy and spectacular lyrics – “it’s only after sixty-eight/that you can really enjoy sixty-nine” – but at eight I knew I was in the presence of life.

By the time my parents carried me back to bed, just a hundred yards and an archipelago of stories away, I was inoculated against gloom for the year. Life was kind, and I was the luckiest blueberry in the bush.

A week after the Carters’ party, someone else’s celebration followed down the block. The bus stop parents never showed at the Carters, and we were never part of the second event. But they had speakers and verve, so the full neighborhood attended unbidden.

When you are young enough to trust that every party is a true party, you sing along even half-asleep. Around my bedtime, the down-the-street strangers unpeeled their annual peak moment. From my pink loft bed, I would laugh out loud and sing with them under my breath: “I’m just a gigolo…”

Bless my parents for attempting to define this term in an eight-year-old’s language. “Well, he is a naughty man who dallies about with many women,” my father said.

“But he ain’t got nobody,” I protested.

“That’s the catch.” Dad missed no educational opportunity. “He’s a cad. He’s in it for himself. He’s” – he gestured theatrically – “just a gigolo. He could be more. He doesn’t need to be so lonely.”

I still laughed out loud, but I felt badly for the gigolo. I was only eight, but I knew that nobody needed to be lonely. Love was patient and kind.

But then, my life was based on a true story. I had the best neighbors in the world.