A Matter of Perspective

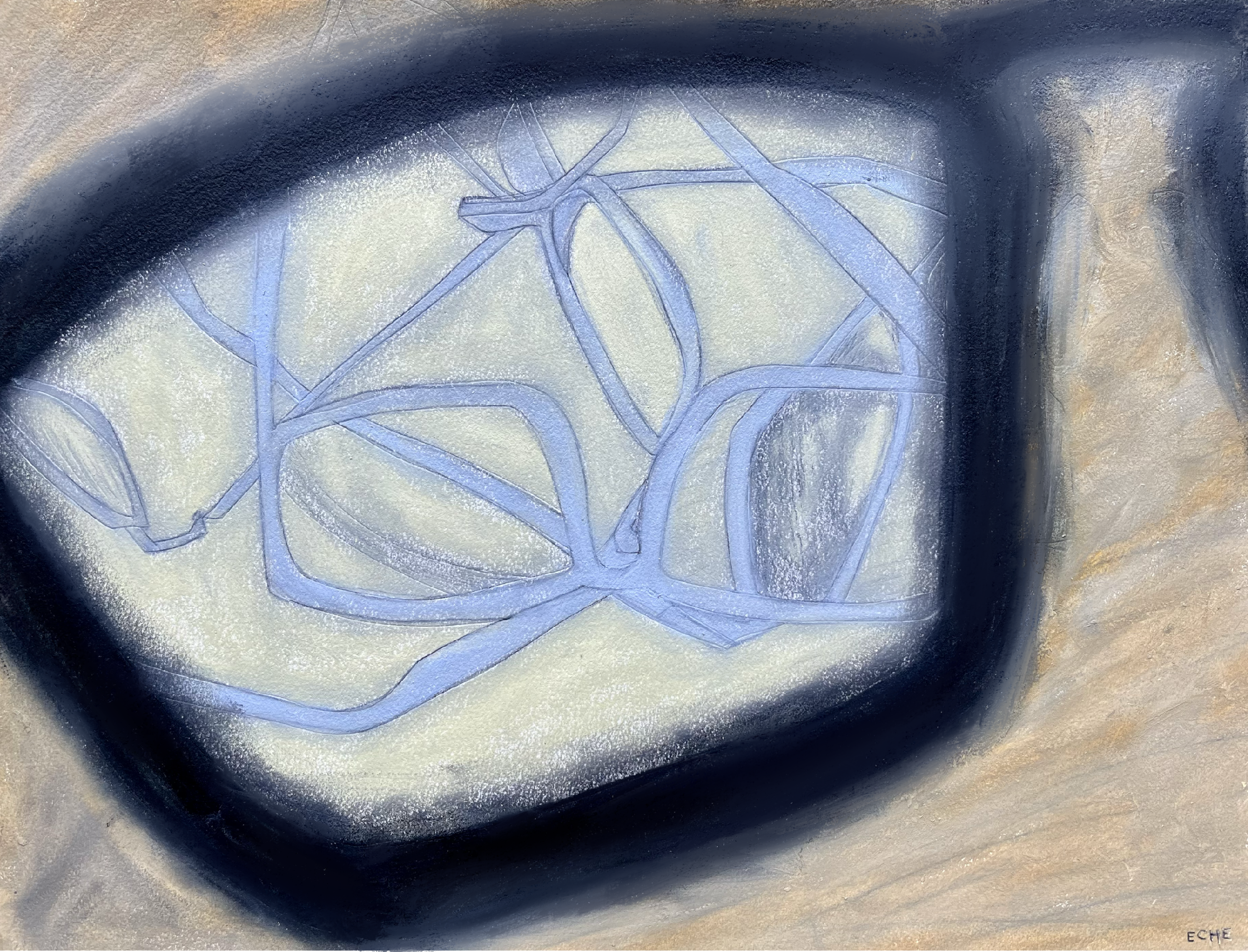

Art by Stephanie Eche

My boyfriend asks me to go shopping for glasses with him because he says he needs my help. It is true that I have spent more time than anyone studying the contours of his face and am well-placed to offer personalized style assistance. But after the first five minutes, I discover that sartorial guidance is not what Timothy means by ‘help.’

‘Help’ means taking photos of him wearing the various sample frames with my phone and then showing him the pictures because he can’t see the mirror without his glasses.

I hardly need to offer suggestions, because the glasses on the side of the shop that has been designated for Timothy and me are all unsuitable. The frames are designed to convey stolid masculinity. Men’s glasses come in either sharp corners and severe angles, round John-Lennon-Harry-Potter glasses with thick rims, or titanium versions of both. There is an abundance of titanium, as if Timothy is going to be wearing the frames on a mission to outer space.

Timothy’s face is composed of gentle curves, his lips are full, his eyes shaded by long, delicate lashes. Timothy is beautiful. Thick lines and hard angles sit poorly upon the landscape of his features; a landscape that does not need to satisfy a commodified idea of manliness.

When we find a pair that gets anywhere close to suitable, I take a picture of him and he takes a picture of the model number on the frames—organized for a return journey once he has made his final decision.

After an hour in two stores, I am getting bored, and we are no closer to finding a pair of new frames. So, in shop number three I start selecting frames that are deliberately bad, chosen to make him laugh when he sees himself in the cell phone pictures.

In a bid to put an end to this process, I cross from the left side of the shop to the right side and check if any of those glasses will suit. The shop assistant—who has ignored us for 20 minutes—materializes at my elbow and hisses, “This is the ladies’ side of the store.”

“They’re glasses,” I tell him, because they are.

“They’re for women,” he says.

“They’re glasses,” I say again, but slower, since this man is clearly an idiot.

“But they’re for women.”

I am about to say something vulgar about where one might wear these particular glasses when Timothy, sensing my unerring ability to create trouble, comes over to stop me.

With him occupying the shop assistant, I am free to spot a good pair of glasses—black frames, but not too thick. Round, but not too round, and the perfect size to show his lashes without swamping his face— even when paired with his Coke-bottle lenses. I disentangle him from the shop assistant, he tries them on, and I snap a picture.

There is a group consultation on Timothy’s eyewear options. After crowdsourcing the decision, he picks the glasses from the ‘wrong’ side of the shop.

When we return to the store to select the frames, model number carefully transcribed from pic to paper, the staff scour the left-hand wall and cannot find them. Their computer tells them they have the frames in stock. Timothy and I exchange a look and communicate, through a gentle brush of fingers against wrist from one to another, that we will let them keep searching.

It takes three whole shop assistants ten minutes to locate the frames on the right-hand wall. One brings them to the counter, apologizes for the delay, and finishes Timothy’s order.

As we turn to leave, she looks from the frames to where she had found them on the right-side wall. Then, somewhat confused, she replaces the glasses on the left-hand side of the store.