Mucking About

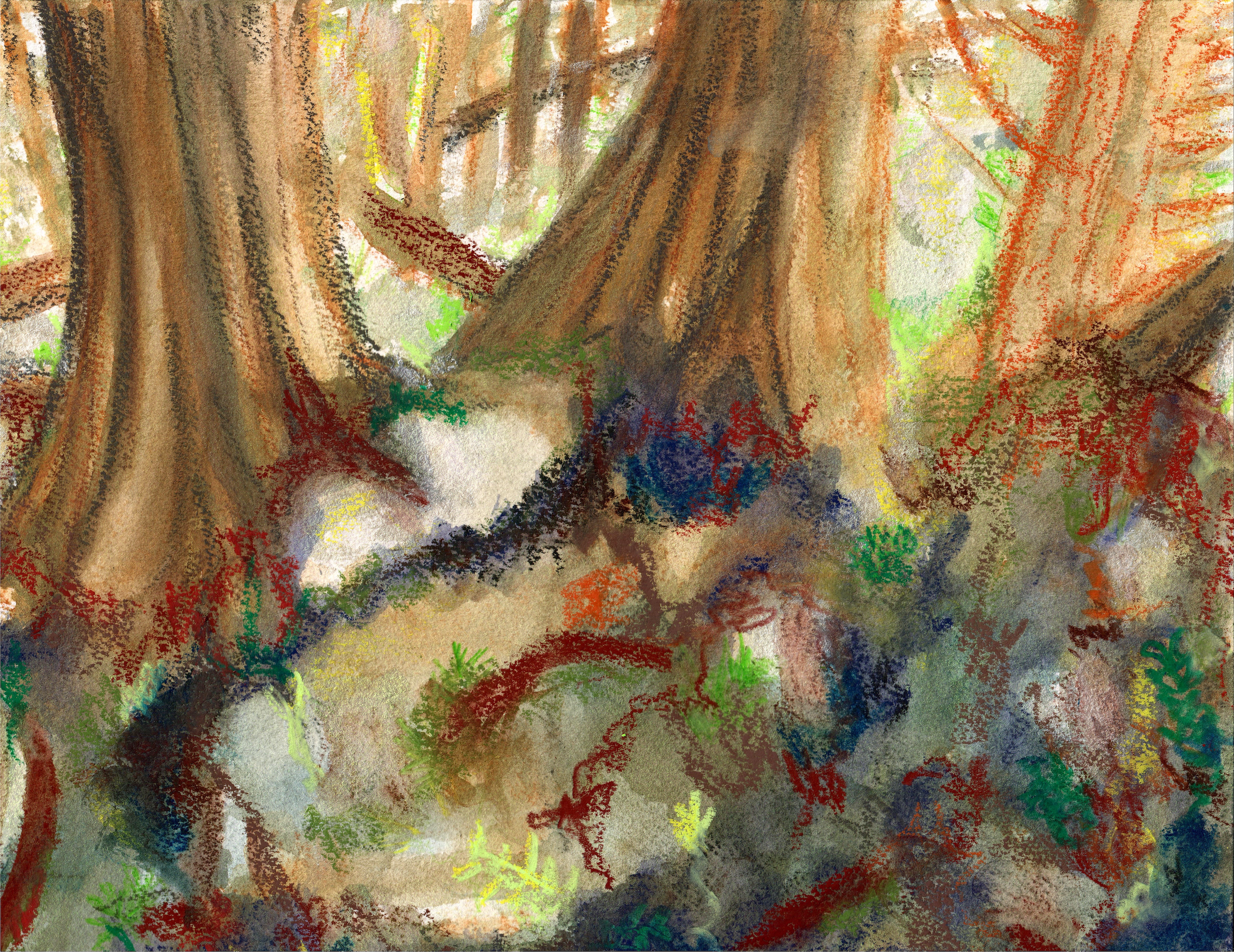

art by Stephanie Eche

With this step, my foot sinks deep, until the muck is within an inch of spilling over the top of my knee-high rain boots. I feel the quick shock of that old, mostly imaginary childhood fear: quicksand. Surely, there was much more quicksand in the movies and cartoons than there ever was in the physical world. Still, the floor of a Northern Red Cedar Swamp is something like quicksand, if my disappearing left boot is any indication.

Minutes earlier, I’d learned that this is not just water, but a kind of soil we’re walking in. It looks to my yet-untrained eye like a pond populated by tall trees, punctuated frequently by hummocks—islands of fallen trees that have formed a foundation for colonies of mosses, wood sorrel, sedges, ferns, more trees. But its depth is puddle-like, mostly; each step into dark water finds a solid-enough purchase a few inches down. The wetlands-specialist my naturalist group is learning from squats and with a long, bare hand scoops, bringing up a palmful of what looks like dirty water. “Muck,” he says. He scoops again, palpates the substance, squeezes it. “Maybe mucky-peat in some places.” He explains that swamp-soil is classified as muck when the organic material it comprises has decomposed beyond recognition. Mucky-peat and peat contain distinct, distinguishable components. This, though, runs easily through his fingers, a well-steeped tea of once-living things. Near the surface, it’s mostly water. Deeper, the sediments are denser, of course. They cling to each other, cling to our boots, releasing them with a sucking reluctance. We move on.

I try to pull the whole thing—leg, foot, boot—out at once, and the force of the muck is strong enough that I rebound and step my right foot from its sturdy hummock into muck, where it promptly sinks just as deep as the left. But not deeper. I’m in luck. The swamp and I seem to have reached an equilibrium, at least in the short term, that chases off the quicksand horrors. But pull as I might, I can see that I’m not going anywhere without taking my feet out of the boots. One hand’s braced on a tree—whether it’s dead or dying or stunted, I don’t have the extra bandwidth to note, just that it feels sturdy enough. One hand braced, I pull my left foot out of its boot and hold it above the muck in a yoga-pose I might call “cat-in-a-bath” while tugging the boot with my free hand. No dice. I can barely get a good hold on the dry edge, let alone find leverage. I realize that the direction of force most likely to free the boot is also the most difficult: away from me. I try pulling towards my body anyway, and the equal and opposite force knocks me off balance enough that both left foot and left hand touch down, soaking both sock and glove. I try again, pulling in the better direction, and the muck releases its hold. Balancing (I’d prefer to think) like a Cirque de Soleil acrobat, I peel off the muck-sock, stuff it in whichever backpack pocket I can reach, get my bare foot back into the boot, and brace now a foot and a hand on the hummock while sliding the right foot out of its trapped boot. This one’s easier, since I’ve learned my lesson for the moment about the physics of force, and, boot freed, both feet inside boots, a little shaky, I pick my careful way along hummocks and fallen trees towards my group, some of whom are just helping another person free her stuck boot from the swamp’s grasp.

I wasn’t here alone, and I’m glad, as, free, my mind plays out a reel of what it would’ve been like to get myself out of the swamp having lost the boots to it. But I hadn’t called to anyone for help. I was embarrassed that I’d stepped badly, and, strangely, believed that I didn’t have the right to involve anyone else in my ineptitude. Yet, I could see clearly enough, the other stuck person had asked for help and those around her rallied right away, pleased to save a fellow struggler. Schooled in the limits of self-reliance, my imagination runs to images of blackened bog-bodies, to all the fallen beings in this muck—which are, I must remind myself, what muck is.