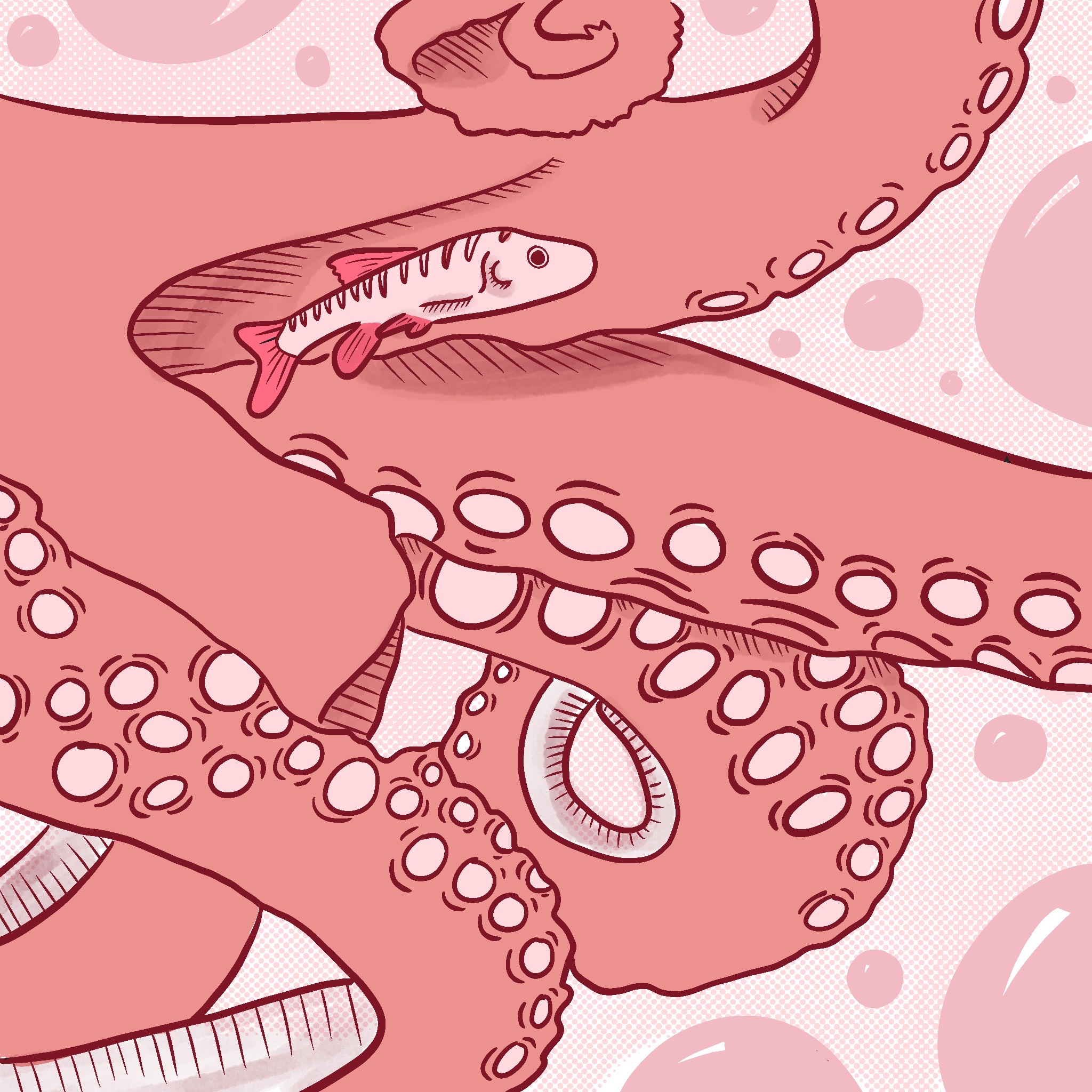

Sea Monster

artwork by Claire Tomasi

In a previous life she’d been a monster living on the ocean floor. She remembered herself well, a coiled mass of dark tentacles, her mouths a series of black, razored beaks. It was a secret she’d always intended to keep until she abruptly told her husband about it one night at dinner. He had been about to take a sip of beer, but instead lowered his glass back to the table. They were seated outdoors at a place called Valleys on a hot summer night, the flow of their fellow city dwellers on the sidewalk embellishing the sudden stillness at their table.

She had just finished her second martini when she confessed it. She set her coupe glass down but held onto it, staring at her fingers on the stem with what looked like regret, her face flushed. Her husband only smiled, waiting for some indication of what was expected of him. He’d never made any great secret of the fact that he’d once been a sardine, though he had also never discussed it with her in detail. After all, the subject of past lives seemed to irritate her.

Nothing bothered her more than being stuck in line at the drugstore while two elderly patrons discussed how they had once been apes, chewing leaves and rustling the canopy.

“I was a gibbon,” one would say, her wide eyes daring anyone to say otherwise. “I flew through the trees like a shot.”

When she’d been single, men had always delivered her their prepared speeches of how they’d been leopards or eagles, going on about the feel of jungle loam under their paws or the thrill of spotting a startled mouse from two thousand feet up. Even if the stories were true, she found them pathetic. Not only because in her life as a monster she had known a strength that made the sly agility of eagles and jungle cats seem like the panicked scurrying of insects, but because she had always told herself that past lives had no bearing on the present, that dwelling on them was only a kind of useless nostalgia.

On her first date with her husband, he had inadvertently revealed in the first five minutes that he was once a sardine. Right away he stopped what he was saying and tilted his head back, his mouth hanging open at the unhappy realization he hadn’t thought to make up something better. She never told him but it was in this moment she decided to see him again. It wasn’t just his endearing and reflexive honesty. His look of embarrassment had also suggested to her that his previous life was not a point of pride that would need to be discussed again and again.

But now after four years of marriage she’d broached the subject on her own. Who could say why? Of course there were the martinis, which she’d drunk quickly in the heat. Perhaps the cold gin and brine had been enough to bring back a life alone at the bottom of the ocean.

Up here there was the constant press of passersby on the sidewalk. She ignored it as a man passing their table swore and laughed into his phone. The siren of a passing ambulance rattled her silverware, but left her unfazed. Whereas in her previous life she would have flung herself at the slightest provocation. Maybe that’s what made the urge to mention it unstoppable, the memory of that fierce solitude compared to the put-upon weariness she felt now at the end of the day.

The elevator in her office building was broken, and so every trip up to accounting had been a four-flight slog reminding her of how difficult it was to pull oneself through a field of gravity with nothing to buoy the body but the naked air. Back in the icy black of the ocean’s floor, her body had been able to pull at the space around her like cloth. She’d known how to tear through it, wrap it around her, perch in a swirl of it. The world had been a palpable emptiness that at any moment she could spring out into. An arrow willing itself into flight. And even though all of this was the exact opposite of how she felt now, tired, hot, the fabric of her blouse sticking to the small of her back, it was as if that strength and freedom, because it had belonged to her once, was hers forever. And maybe it was the urgency of that feeling that had caused her to lean over the small cafe table now and touch her husband’s arm, expanding her confession to explain that she had been a creature of unthinkable strength and violence, sucking up the cloudy remains of pulped bodies in deep caverns without light.

Her husband blinked his small, trusting eyes and was almost ready to laugh until he saw the stricken look on her face.

“Well,” he said, placing her hand on his cheek, “we’re here now.”

She tugged his ear before taking back her hand. She was grateful for those words but the truth was that behind her own insistence that one’s past life had no bearing on the present was the lurking fear that perhaps it did. When she was younger she’d loved a man who’d attributed his fear of thunderstorms to the fact that he’d once been a golden retriever. Her grandfather had been some long extinct species of wading bird and when he wasn’t paying attention he would sometimes draw up his right leg to stand on one foot. Her mother had been the fantail goldfish in the gilded table aquarium of a 17th century French aristocrat and now whenever she swam in their family’s backyard pool she had a way of darting down from the surface of the water with an awkward but powerful waggle of her backside.

These echoes of former lives troubled her because her clearest memory of her existence as a monster, more than her strength, had been her pure and all-consuming selfishness. So while the sight of her grandfather standing with a cup of coffee in flannel trousers in his kitchen, his right root resting unselfconsciously on the thigh of his left leg, was seen as charming to those who knew him, to her it was an indictment against her deepest nature.

Sitting alone in her apartment holding a book in her lap, she was sometimes exhilarated by the memory of all that apathy and solitude. The book she was only pretending to read would start to feel lighter. If she let go, it would have begun to float. Her heart pounding, she would shake herself out of it, reaching for her phone to call a friend or text some small thing to her husband in an effort to pull herself back up to the present.

These feelings of the past felt so much stronger than her simple love for her friends and family and even her husband that she was often sick with dread that perhaps the memory of her selfishness was more real than her love. Whenever her husband spontaneously declared his affection for her, as was his tendency, she would let her pleasure at his sentiment be dulled by the question of how much happier it would have made her if she were not secretly and more truly a monster buried beneath an ocean. She was, she told herself, an imposter only going through the motions of affections that weren’t really her own, but the product of a here and now that was too oppressively complex and befuddling to resist.

She was quiet throughout the rest of dinner and in their bed that night she pulled herself through the dark and into her husband’s arms where she wept and apologized.

He asked her what she was apologizing for, but just held her when she couldn’t explain it.

Crying in his arms, she thought of how vulnerable he must have been in his life as a sardine and felt an overpowering need to protect him, to scoop him up in her cupped hands, little fish, and hold him to her chest. She thought, as if pleading with herself, Of course I love him. She felt suddenly proud of that love, defiant.

Recalling her strange confession at dinner, her husband thought he finally understood and gave her shoulders a squeeze.

“It must have been lonely,” he said, “being a sea monster. At least we sardines had each other.”

She had to hold back a sob as she said, “I would have eaten you all if I had the chance.”

To her surprise this made her husband laugh.

“I don’t think so,” he said. “My school was fast and we could all change direction at the same time. I’m still not sure how we did it.”

The two argued about whether or not she’d have been fast enough to catch him until she finally joined him in his laughter and gently bit his shoulder, wrapping her legs around him as she did so. If her legs had turned into tentacles in that moment, she didn’t think it would have surprised him in the least. She may have never said the words “sea monster” to him before but everything of importance he already seemed to know. If she had once been immense and ruthless, he had been small and quick. Just like that, her old solitude seemed suddenly harmless, one form of life among many.

The two fell asleep and were drawn back into memories of their former lives, as was common for dreamers. Already she was thousands of miles away, but could still perceive her husband’s twitching as he slept. In his part of the ocean he was darting, giddy with panic, snapping this way and that with his school. Meanwhile she unfurled herself along the ocean floor, giving herself space, her countless limbs spreading and undulating in preparation of something powerful and mysterious.