Brazil Is Not for Beginners

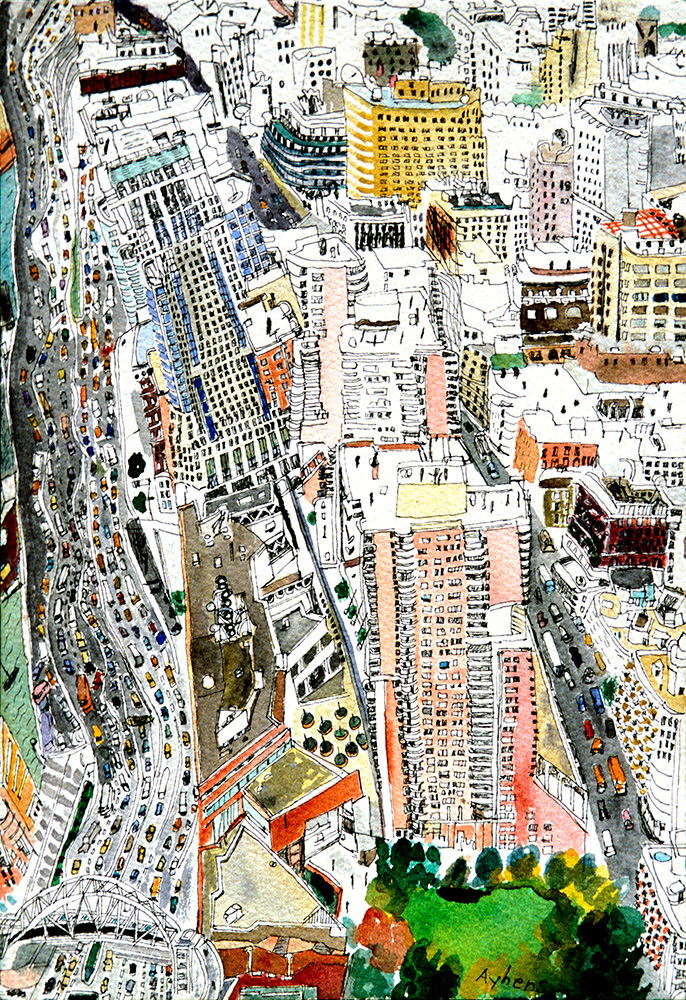

artwork by Olive Ayhens

Revelers in devil horns, feather boas, and not much else but glitter celebrated against a backdrop of decaying Beaux-Arts buildings. Downtown Rio is normally deserted and dangerous on weekends, but this Carnival Saturday the urban art tour I’d signed up for coincided with a massive street party.

My obsession with Brazil began inauspiciously at age 20 with Wild Orchid, a trashy erotic thriller set in Rio. Ludicrous plot aside, the gaudy Carnival scenes set against peeling colonial splendor mesmerized me. Thirty years later on my third visit to the country, I was finally experiencing Carnival in the flesh.

I was staying in Rio for a month taking Portuguese classes in Ipanema. I loved the musical and expressive Brazilian dialect, a rich stew of Portuguese, African, and indigenous influences.

Together with students from my language school, I had even marched in a sequined parade at the Sambadrome. We went on at 4 a.m. after hours of delay due to rain. I desperately needed to pee, but that had become impossible seven hours before when I donned my costume. When the Sambadrome gates opened, an adrenaline surge erased our fatigue. I adjusted my heavy, feathered headpiece, pasting a smile on my face. TV cameras swept over us. Mouthing nonsense syllables when I forgot the lyrics, I traversed Rio’s fabled parade ground with my clumsy gringo shuffle.

Now, I was exploring a different side of the city. Street art is legal in Rio and provides a potent form of artistic and political expression. I’d signed up for an urban art tour to decipher the hidden meanings of the images splashed across the city’s canvas.

It looked like I was the only participant. Uneasy about being alone, I sheltered in a McDonald’s entrance as I waited for Ana, my guide. She emerged from the crowd, slipping off a sparkling half-mask.

Ana, a slim twentysomething brunette, was a lifelong carioca, or Rio resident. This former design student had become one of the city’s most passionate urban art promoters.

Ana introduced me to Rio’s guerrilla art with a two-story mural portraying musician and activist Gilberto Gil in the main square. Despite prison and exile, Gil spent 50 years protesting the injustices perpetrated against Brazil’s poorest.

I asked if it was safe to photograph with my smartphone. “No problem,” Ana replied.

We strolled towards Lapa, Rio’s nightlife district. The party had started at dawn to avoid the heat, and by midmorning now Carnival detritus littered the cobblestones: water bottles, metallic confetti, broken plastic tiaras.

Ana and I paused before a poster series of mutilated baby dolls representing the violence and neglect suffered by Brazilian children of African and indigenous descent. I snapped a photo and then gasped as a strange hand closed over mine.

A wave of shirtless teenage boys surrounded us. This was a mass robbery so common it had a name, arrastão, or dragnet. In these attacks, gangs of youths descend from impoverished hillside favelas and sweep an area, mugging anyone in their path.

I managed to hold on to my mobile phone in the tug-of-war, only to have another hand and then a third try to snatch it. The arrastão rippled around us, but a wrist strap saved the device from being yanked away. My high-pitched scream reached me as if from a distance. The boys finally ran off without their prize.

A group of young men in tutus leaning against a kiosk beckoned us into their midst and closed ranks. They hugged us, giving me sips of water, the traditional Brazilian remedy for stress. “Are you OK?” Ana asked. She hadn’t been touched during the robbery. I was the target, likely as much for my gringo looks as my phone.

“Good job!” The men congratulated me in broken English for hanging onto my possessions. We hid in their circle until we were sure the gang was gone.

Ana took me to a shop to buy water. My bottle had rolled away during the attack and been snapped up by one of the boys. A water shortage due to bacterial contamination was punishing Rio’s poorest residents that summer with little means to buy bottled water.

I told Ana we should cancel the tour. “Let’s go to this nearby hotel. It’s safe,” she suggested. Ana mechanically pointed out the vivid murals decorating its interior, but neither of us was really in the mood to appreciate them.

We climbed to the rooftop bar. Ana drew out a tobacco pouch and rolled a cigarette with shaking fingers. “I’m so sorry,” she said. “I never had anything like this happen before on a tour.”

I gazed down at Lapa’s famous white arches thronged with samba-dancing partiers sipping Brahma beers. The pulsing percussion beat was fainter here. My heart stopped thudding in my chest.

“Let’s finish the tour,” I said, pulling out my wallet to pay for my drink. “Can you pay me now?” Ana asked.

Over the next hour, Ana and I explored Lapa’s surreal murals: Baboon businessmen joyrode through the toxic sludge of the Brumadinho dam disaster caused by negligence and corruption; a policeman wearing a crucifix held a gun to the head of a kneeling Afro-Brazilian boy; a teen with a cast on his arm decorated with “Pro Life” and “100% Jesus” slogans clutched a rocket launcher.

We finished the tour without incident. I slumped into my seat on the metro ride back to my cozy homestay in Copacabana.

In the weeks to come, after this lesson on Rio’s street art, I spotted works everywhere I went. Even chic Ipanema had protest art sandwiched between the boutiques patronized by residents with pedigree dogs. I reflected that these glossy canines almost certainly enjoyed a more comfortable life than the street-dwelling humans lining Ipanema’s mosaic sidewalks.

Brazilians I told about the arrastão were sympathetic but unsurprised. Visitors can’t always escape the violence and crime underlying Brazil’s seductive beauty and warmth, the sad legacy of inequality and racism left by centuries of enslavement. Arrastões and other street crimes pick up in summer when more than 2 million tourists descend on Rio for the world’s biggest party. I felt lucky to have escaped with my phone and no worse injury than a raw wrist as a Carnival souvenir.

Guidebooks to Brazil tell you it’s best to surrender your belongings without resistance in a mugging. However, sometimes we react instinctively. On a previous visit to Brazil, a skinny, shirtless teen had jumped me at the beach. I had battled him for my backpack but then let go when he reached into his board shorts, announcing “Tenho faca” —”I have a knife.”

That time, too, the worst of Brazil had immediately inspired the best. Nearby drink vendors clucked over me, shepherding me to a folding chair and giving me a glass of water to calm my tears.